|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Big Trees & Totem Poles |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Aboriginal Heritage Trees |

|

Haida Gwaii Totem Poles |

|

| |

Skeena River Totem Poles |

|

The Vanishing of Totem Trees |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Indigenous Heritage Trees

Totem poles are carved from large red cedars, hundreds of years old. These irreplaceable indigenous heritage trees are vanishing due to industrial logging. Guujaaw, a traditional carver and the president of the Council of the Haida Nation, is at the forefront of a movement to stop the industrial destruction of ancient cedar trees (right). In a petition submitted to the UN Convention for Biological Diversity in 2003, he wrote: "We will make a stand now or lose our culture. There is no substitute for a 500 year old cedar for a totem pole or an 800 year old tree for a canoe. Having said that, a living tree is of more value than any cultural object. The North Pacific Cultures and their relationship to the Earth is not only worthy of survival but essential to understanding humanity's place on this Earth in this century." |

|

Guujaaw, 20 May 2004

Photo: Union of BC Indian Chiefs |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

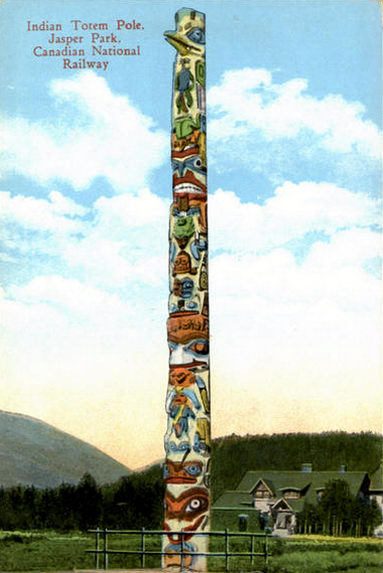

"Indian Totem Pole," Jasper, Rocky Mountains.

Old postcard, c. 1940 |

|

Totem poles were appropriated early on after they were discovered by colonists on the Northwest Coast, first they were looted massively, then they were banned as settler society attempted to root out native culture. Following this dismal period of Canadian history, totem poles were resurrected to increase tourism revenue and promoted as a symbol of Canada, serving as cultural ambassdors across the world. Today the art of totem pole carving has been reclaimed by First Nations as a monumental and potent landmark of sovereignty.

An indication of this welcome change is the return of the historic Raven Totem Pole (left) which was removed from Haida Gwaii by the Canadian National Railway Company in 1919. It was painted in gaudy colours and erected at the railway station in Jasper to promote tourism, though the native people in the Rocky Mountains had no tradition of totem poles. The Haida totem pole was carved in Old Masset in the 1870s, probably by the master carver Simeon Stiltla (1833 – 1883). It is topped by a raven figure and served as a memorial pole, commemorating a deceased chief.

Over the years, the Raven Totem Pole was left to deteriorate until 2000 when it was purchased from the railway by Parks Canada which proclaimed it as beyond repair. Not so, said George MacDonald, a Haida art expert who saw the pole as valuable and rare, a "national treasure." He advised that it be restored and returned to the Haida to support the reclaiming of their cultural heritage. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Totem Poles Admired Worldwide

Totem poles are today seen in locations around the world, far from the Northwest Coast forest landscape and cultures in which they originated. The art of totem pole carving is a flourishing contemporary art form and an expression of indigenous identity. Totem poles are carved from big trees, typically densely grained ancient western red cedar trees native to North America.

These monumental cedars are an integral part of the rich and complex relationship to nature that evolved over thousands of years among the indigenous Northwest Coast peoples – the First Peoples. Carved from trees that were nurtured in ancient forests and sustainably managed for thousands of years before colonization, totem poles are an environmental art form.

Nisga'a Norman Tate's "Big Beaver Totem Pole."

Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois |

|

Nisga'a carver Norman Tait, 1987.

Photo: University of British Columbia

Norman Tait was born in the Nisga'a village of Kincolith on the Nass River in 1941. He is a master artist and has carved some of the most outstanding contemporary totem poles in the world. A photo shows Tait carving a totem pole from a huge cedar log outside Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver in 1987 (above). Today, a couple of decades later, he laments about how difficult it has become to find large enough cedar logs for carving.

Tait's 167 m (55 ft) totem pole, "Big Beaver" stands proudly in front of the Greek collonaded Field Museum in Chicago (left). It was raised on Earth Day, 22 April 1982. "The Nisga'a totem poles stand tall to show the world who we are. Every figure on a Nisga'a totem pole has a different appearance and meaning" Pts'aanhl Nisga'a |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Left: Book cover of Challenging Traditions (2009) by Ian Thom showing a carving in yellow cedar, the most sacred tree, native to Vancouver Island, by Haida artist Don Yeomans. There must be a boycott of all commercial and non native trade in yellow cedar. Like the ancient trees in BC, the wild salmon are vanishing as a result of industrial forestry. Right: From the book Challenging Traditions, a carving by Glenn Tallio, b. 1939 Nuxalk Moon Mask, 2000 red cedar, acrylic, cedar bark. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

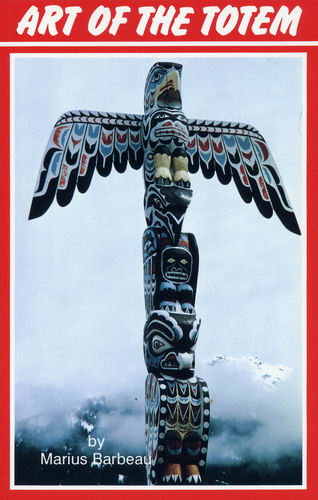

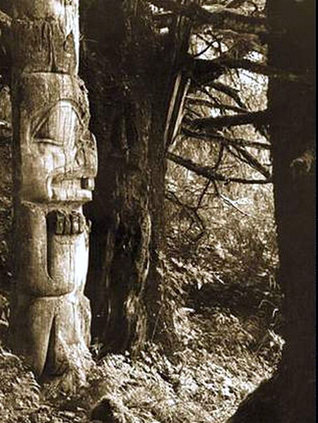

From Marius Barbeau: Totem Poles: A Recent Native Art (Geographical Review, 1930).

"Not even a remnant of the famous clusters of former days remains among the Haidas of the Queen Charlotte Islands. Barely a few are still left among the Bellacoolas, the Kwakiutl, and the Nootkas of the west coast of British Columbia; in a few years these will have totally disappeared."

"The only collection of poles that still remains fairly complete is that of the upper Skeena, in British Columbia, a short distance southeast of the Alaskan border, from I50 to 250 miles inland, at the edge of the area where this art is practiced. Nowhere else but on the Nass, where a number of poles also survive, are they to be seen far inland. The Canadian Government and the Canadian National Railways a few years ago inaugurated the policy of preserving the Skeena River poles in their original location."

"These picturesque creations, however, can be seen to full advantage only in their true home, at the edge of the ocean, amid tall cedars and hemlocks, and in the shadow of lofty mountains. With their bold profiles, reminiscent of Asiatic divinities and monsters, they conjure impressions strangely un American in their surroundings of luxuriant dark green vegetation under skies of bluish mist." |

Sadly, industrial resource exploitation has not been thwarted by the world renown of the indigenous Bella Coola (Nuxalk) culture. In 2009 one of the most productive sites of Northwest Coast culture, the ancient Nuxalk community at Talyu – most famous for its Raven house entry pole (left) – was invaded by heli–loggers and their log dumps. Recognition is owed to the Nuxalk people, many of them Elders, who have courageously defended their land and waters against the relentless pillaging by extraction companies such as Interfor, operating with full government complicity.Land Infringement at Taleomey Narrows |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

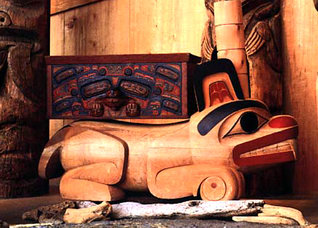

Right: "This sculpture of a Beaver by Jim Hart is in the form of a traditional manda'a, or coffin support, used to display the burial chest of a high-ranking chief in his burial shed"

Canadian Museum of Civilization. It was commissioned for the Grand Hall and installed in 1995.

"The cedar tree has kept us alive for many thousands of years" says Haida carver Jim Hart "We use it for clothing, canoes, housing. In return, the Native peoples of the Northwest Coast have always treated the cedar tree with the greatest of respect . . . I want my children, and their children's children and down the line to keep on with our deep connection to the cedar tree, which is so important to all of us, our lands, Native and non Native alike. We can't let the cedar disappear from our forests"

A Vanishing Heritage. |

|

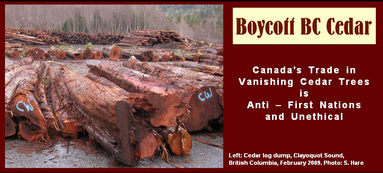

Totem Poles and Cedar Trees The destruction of BC's last surviving cedar trees for commercial wood products and pulp and paper is an abuse of indigenous rights and a case for international condemnation of Canada, a country whose oppressive colonial history continues unabated in the form of natural resource exploitation.

Carving in yellow cedar by Jim Hart, 1995.

Photo: Canadian Museum of Civilization |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Tony Hunt (born 1942) is a Canadian First Nations artist of Kwakwaka'wakw ancestry noted for his work carving totem poles. He was born in 1942 at the Kwakwaka'wakw community of Alert Bay, British Columbia. He received early training from his maternal grandfather Mungo Martin. He is also a descendant of the renowned Native ethnologist George Hunt. After Martin's death in 1962, Hunt became assistant carver to his father Henry Hunt at Thunderbird Park in Victoria, B.C. His brothers, Stanley Hunt and Richard Hunt, are also professional carvers. In 1984 he carved a replacement totem pole, called Kwanusila (Thunderbird), for one his ancestor George Hunt had made for the people of Chicago.First Nations have a long history of protesting the government's forest policies. When it ammended the BC Forest Act in 2006, the lumber industry gained a new and insidious way of gaining control over contested First Nations land through secretive and illicit deals designed to make a quick buck. Kwakiutl Protest

|

|

Kwakiutl Tony Hunt, protest, 2007.

Photo: G. T. Wm. Edwards |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Thunderbird Totem Pole by Kwakiutl Tony Hunt — Raised 21 May 1986 in Chicago, Illinois |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Parliament of Canada and a totem pole.

Tourist postcard

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) was signed at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 1992 and entered into force on 29 December 1993. It is the first global agreement to cover all aspects of biological diversity: the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the use of genetic resources. The Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (SCBD), based in Montreal, Canada, was established to support the goals of the Convention. The CBD Secretariat. Based in Montreal, it operates under the United Nations Environment Programme.

Welcome to the Traditional Knowledge Information Portal, which has been developed by the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity in order to promote awareness and enhance access by indigenous and local communities and other interested parties to information on traditional knowledge, innovations and practices relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity. It aims to provide useful and timely information especially as traditional knowledge in relation to the programme of work for Article 8(j) and Related Provisions.

mmmmmm

mmmmm |

|

Above: Totem Pole just north of Belmont Harbor, Chicago, Illinois USA Left: "Kwanusila, the Thunderbird, is an authentic Kwagulth Indian Totem Pole, carved in red cedar by Tony Hunt of Fort Rupert, British Columbia. The crests carved upon the totem pole represent Kwanusila, the Thunderbird, a whale with a man on its back, and a sea monster. Kwanusila is an exact replica of the original Kraft Lincoln Park Totem Pole, which was donated to the City of Chicago by James L. Kraft on June 20, 1929, and which stood on this spot until October 9, 1985. Kwanusila is dedicated to the school children of Chicago, and was presented to the city of Chicago by Kraft, Inc. on May 21, 1986."

Above: Kwakiutl Thunderbird Logo

Convention on Biological Diversity

United Nations Environment Programme |

mmmmmm

mmmmm |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

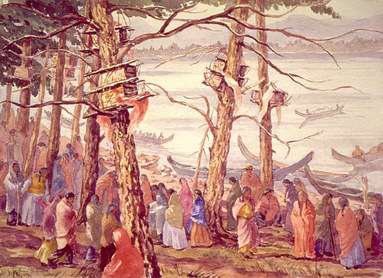

Tree Burial at Fort Rupert.

Painting by Joanna Simpson Wilson

During the past century, industrial logging has dramatically reduced the number of trees suitable for totem poles, dugout canoes and other forms of Northwest Coast carving traditions. In addition, culturally modified trees (right) such as bark stripped cedars are being indiscriminately cut down. These aboriginal heritage trees, which include "totem trees," are rare and endangered and need urgent protection.

In 2005, to address the difficulty of finding monumental cedar trees for totem poles and other carving traditions, and to explore legislative means to preserve these aboriginal heritage trees for future generations, a Cedar Symposium "Humiis T'ikwitleth" was organized in Port Alberni by the Hupacasath First Nation." The Cultural and Archaeological Significance of Culturally Modified Trees:

Sacred Cedar.

|

|

Most of British Columbia (BC) is so called "Crown" land, considered public land to be held in trust by the government. In fact, this land has never been given up by the indigenous peoples and their Aboriginal Title and Rights remains an unresolved legal issue. BC's economy has been built on the forest industry and the BC government continues to back the interests of transnational logging companies over and above the land title and rights of First Nations and settler communities that depend on longterm sustainable forestry.

Culturally modified tree, a bark stripped cedar.

Photo: Philipp Kuechler |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Ancient cedar, Quatsino, Vancouver Island, 2003.

Photo: Joe Foy

Save the Klaskish Giant One of the last unlogged watersheds on the Pacific Coast is on the northern tip of Vancouver Island. Recreational maps of this area indicate parks by big tree icons but most of this so called Crown (public) land has been leased for logging. Big trees in Quatsino Territory are endangered. See the shocking photos taken by Joe Foy: East Creek Massacre 2003. |

|

This enormous cedar grows in the wild Klaskish Valley known also as East Creek and is endanged with extermination by logging. With its heavy limbs, it is the 8th largest western red cedar on record. The person seen in the above photo is standing 6 m above the base of the massive trunk which has a huge hollowed centre.

Ancient cedar, Quatsino, Vancouver Island, 2003.

Photo: Joe Foy |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Slash and burn of ancient cedars, Washington, 1909.

Photo: University of Washington Libraries

Big Trees as Commercial Products In just over one hundred years of settlement, land clearing and industrial logging, the ancient cedars and other magnificent big tree species native to the Northwest Coast are on the brink of disappearing. The big trees are gone from Oregon and Washington and the same destructive pattern is being repeated in British Columbia. See the Suzuki Foundation research data and photos of the logging sites, including Haida Gwaii. |

|

Weyerhaeuser clearcut, Haida Gwaii, 2004.

Photo: David Suzuki Foundation |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

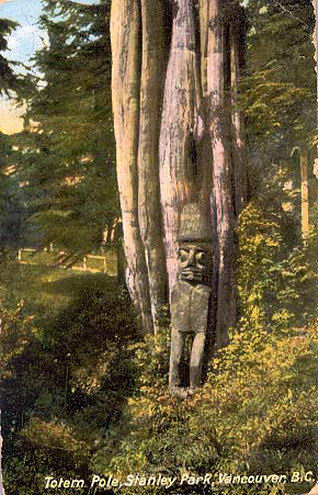

The term "totem pole" is recent and has come to refer to carvings which had different terms and functions in their original settings. Historically there were many types of poles: some served as doorways to houses; others as interior support posts; memorial poles honored deceased chiefs and mortuary poles contained the coffins of important people. Crest or heraldry poles give the ancestry of particular family, history poles record the history of a clan, and legend poles illustrate folklore or real life experiences.

The history of Stanley Park is marred by the displacement and dispossession of the Coast Salish Peoples: villages were demolished, fishing grounds stolen, ancient middens and burial sites desecrated. Following its questionable legal wins in the 1920s against the people it labelled 'squatters," the City of Vancouver concocted an "Indian Village" as a popular attraction. Only the totem poles were installed. Nearby the BC Lumber Manufacturers Association built a "Lumberman's Arch" in 1952 on the site of the ancient village Whoi Whoi. This was a crude attempt to glorify the industry that had made vast profits from the plundering of the big cedar trees necessary for Northwest Coast art and carving traditions. While the pretentious monument to the deforestation of BC fell into obscurity, the totem poles remain the most popular tourist attraction in BC.

Western red cedar, Sitka spruce, Douglas fir and hemlock are native big tree species that have been recorded as growing up to 2,000 years. It is a tragic loss that so many of the big trees have been decimated by industrial logging. |

|

"Totem Pole, Stanley Park, Vancouver, BC."

Photo: old postcard |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

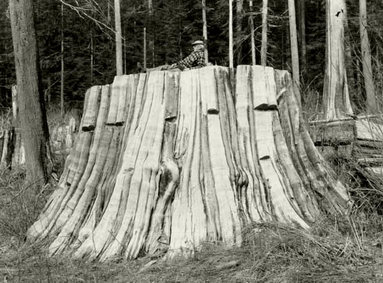

"MacMillan Bloedel Eco-System."

Painting by Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun

One ancient Sitka spruce tree on Lyell Island (Athlii Gwaii), the site of the famous 1985 Haida blockade to prevent industrial clearcutting. During both WWI and WWII, wood from the ancient Sitka spruces of Moresby Island was in heavy demand to supply the industrial production of military airplanes in Seattle. A photo showing a huge stump is the only evidence of one of the giants felled in 1938. Note the springboard notches left in the stump. |

|

Left: "MacMillan Bloedel Eco System Destroyers and Their Preferred Weapons." This 1994 painting of a barren landscape of big tree stumps is by a contemporary indigenous artist and expresses his view of the forest industry with its lies about sustainability and ecological stewardship. The rampant clearcut logging of First Nations land is a theme that runs through his work. He says "As sovereign caretakers of the land, our forebears were always the protectors of the biosphere" Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun.

MacMillan Bloedel's reputation as a destroyer of ecosystems was broadcast worldwide during the logging protests at Clayoquot Sound in the 1990s, but the company has laid waste to the magnificent temperate rainforests of BC ever since it was founded in 1919 by the villainous Harvey MacMillan, BC's first Minister of Forestry.

Stump, Moresby Island, Haida Gwaii, 1938.

Photo: BC Archives |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

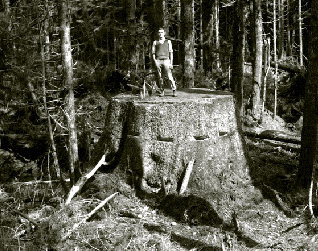

"Cedar stump 60 ft circumference, Sedro, Wash. 1890."

Photo: University of Washington

Already by the turn of the century the big trees of western Washington had become memories, preserved only by the many photos taken to show the heroic strength of the men who felled them. The massive stumps which remained after the forest land was burned off became curiosities, something to marvel at and pose beside for a souvenir photo (above).

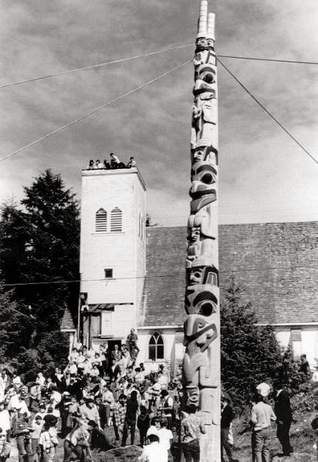

Masset is an ancient village on Haida Gwaii, well known for its astounding cultural heritage, especially the magnificent totem poles and long houses made of monumental cedars. The photo to the right shows a totem pole raising ceremony in Masset on 22 August 1969, the first such event to occur in 80 years. The pole was carved by Robert C. Davidson, an artist from the Haida community of Masset.

"Through his grandmother Florence Edenshaw Davidson, he was linked to artists Charles Edenshaw and Albert Edward Edenshaw. His grandfather Robert Davidson Sr. was a carver and a hereditary chief of the town of Kayung, and his father, Claude Davidson, was a carver who inspired his sons Robert and Reg (who is an artist in his own right) to express their heritage through art and other cultural activities, including dancing" Canadian Museum of Civilization. |

|

Totem pole raising, Masset, 22 August 1969.

Photo: University of British Columbia |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

20,000 images of totem poles donated to the Burke Museum in 2001 by photographer Adelaide DeMenil. The photos can be browsed in 35 galleries of Haida, Tlingit, Kwakwaka'wakw and Tsimshian totem poles organized by location; from Alert Bay and Bella Bella in British Columbia, to Wrangel in Alaska. Includes photos of totem poles in the George Thornton Emmons Collection and the Viola Garfield Collection. From University of Washington and the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture.

Totem poles at Skidegate, Haida Gwaii, 1878.

Photo: Archives Canada (G. Dawson) |

|

"Haida Pole and Forest," 1966.

Photo: Adelaide de Menil

Big trees and totem poles are essential to indigenous cultural identity and to the process of establishing Aboriginal Title and Rights. The fight to preserve monumental cedars for Northwest carving traditions cannot be separated from the art of totem poles. Likewise, the emotional issue of repatriation cannot be separated from totem poles. Historically many totem poles held human bodies, parts of which were collected by museums and private collectors along with indigenous artifacts. Archival photos of the Haida village of Skidegate on Haida Gwaii show the prominance of monumental poles (left), some of which serve as caskets. In the US, the landmark ruling, the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, requires excavated cultural items be returned. The Haida have initiated a number of proceedings to ensure that ancestral remains are brought home to Haida Gwaii be buried. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Museum of Anthropology, 2009.

University of British Columbia

For scholars of cultural history, the specialized genre of totem poles and Northwest Coast art "offers a compelling example of how the interconnected processes of appropriation and representation alter, modify, or even create anew elements of Native culture" Aldona Jonaitis, anthropologist, University of Alaska. |

|

Totem poles have been collected and valued as scientific and ethnographic specimens, as historical artifacts and as objects of art. The revival in Northwest Coast carving traditions has meant that today, in locations around the world, totem poles from the Canadian province of British Columbia can be seen as objects on display in cultural museums and as public sculpture.

Totem pole hall, 1971.

BC Provincial Museum, Victoria |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

The totem pole book was published as two volumes in 1950 in Ottawa, Canada, by the Department of Resources and Development, and the National Museum of Canada. It is the summary of research conducted from 1915 to 1947 on the Northwest Coast. The frontispiece maps are divided into nine distinct cultural and geographical areas identified as: Tlingit, Haida (Kaigani); Haida; Tsimsyan (Niska); Tsimsyan proper; Tsimsyan (Gitksan); Kwakiutl; Nootka; and Salish. Within these geographical areas the map identifies by number the 84 indigenous villages which had totem poles. |

|

Nuu chah nulth groups.

Vancouver Island, BC |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Totem poles cannot be proclaimed to represent indigenous cultural survival when such abuse remains endemic and when the ancient cedar trees and forests in which indigenous Northwest Coast culture is embedded continue to be obliterated by unscrupulous logging companies.

mmmmmm

mmmmm |

|

Gold Harbour log dump, 2009.

Photo: Flickr |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

"In most art contexts, the word 'replica' means copy. The difference between possessing a replica and an original is the difference between owning a map of a place and owning the place. With art made by Northwest Coast peoples, however, the status of objects is always in motion. Poles and house posts decay and are replaced by 'replicas.' The concepts of original and copy are therefore fused, since both are part of a cycle that extends back to ancient times" Regina Hackett (Seattle Post Intelligencer).

Kwakiutl artist Richard Hunt says that his art should be recognized as cultural property: "the things that I do come from our culture. These are things that we own. We go to our Elders to ask them what we can do, and we don't do dances, animals or mythical creatures that don't belong to us. If we did that the Elders could cause us shame, or the owners of these could come and cause us shame and we'd have to rectify the situation." |

|

Haisla carver Lyle Wilson.

Photo: Museum of Anthropology |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

mmmmmm

mmmmm |

|

mmmm

mmmmmmm

mmmmm

mmmm

mmm

mmmmmm

mmmmm |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Henry Chipps carving, 2007.

Photo: Karen Wonders

|

|

Henry Chipps (2007), first graduate of the Indigenous Governance Diploma Program birth home on Mission Island, Kyuquot "I was born in Kyuquot; I’m hereditary chief of Clo oose, and I’m a Beecher Bay Band member." |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

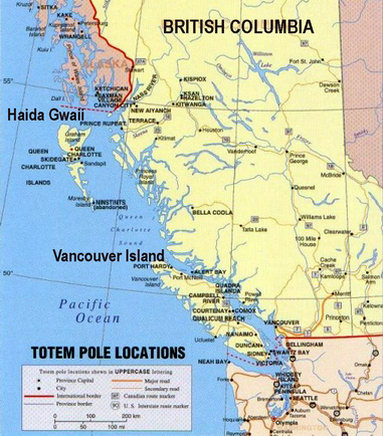

Totem poles locations.

British Columbia, Canada

The greatest number of in situ (in the original place) totem pole sites in the world are in BC. To truly appreciate these monumental sculptures, they need to be seen in the environment where they originated, such as the ancient Aboriginal villages on the Skeena River in northern BC and on Haida Gwaii, an archipelago off the Pacific coast. |

|

Totem poles originated mainly in the cultures of three coastal tribes – Haida, Tlingit and Tsimshian – whose communities are located between Vancouver Island and the Alaskan penninsula. First Nations territories are the sheltered islands, bays and fjords in British Columbia and southeast Alaska as well as the inland river valleys. Every territory has its own languages, traditions, and cultural identities. Carving styles and functions of totem poles vary according to tribe and family.

Northwest Coast cultural areas.

Map: Canadian Museun of Civilization |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

A revitalization of Northwest Coast art began in the late 1950s with a new generation of carvers who relearned their histories and languages and used their art to assert their political identities and rights. "The totem pole in its present sense is a powerful representation of past histories but its symbolic power continues into the present. Poles are being put up to represent families, lineages and histories – they're not just being put up because they're great pieces of art to look at" Bill McLennan, curator, Museum of Anthropology.

"There is in the state of New York a magic place

where Haida totem poles stand tall and free . . . In this place, 'Three

Variations on Killer Whale Myths' [right] are displayed not in the dim

light of some supposed mystic past but fully revealed as confident participants

in the contemporary world" Robert Davidson. Note the woman in the photo

for scale to get a sense of the enormous size of the cedar trees from which

these poles were carved.

Germany regularly features the Northwest Coast art and indigenous culture that is promoted by Canada's Foreign Affairs & International Trade. Examples are numerous and include a totem pole by Tony Hunt raised in Bonn in 2004, and in a red cedar box by Calvin Hunt purchased for the new Canadian Embassy in Berlin. |

|

"Three Variations on a Killer Whale," NY.

Photo: Robert Davidson |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

"Raven, Salmon and Beaver," Uttersberg, 1990.

Photo: Jens Thuresson

Welcoming guests to Galleri Astley is a large sign with a Haida motif:

Raven Comes to Uttersberg (right). |

|

Totem poles have been commissioned as works of art for public and private places throughout the world. Although deprived of their original meaning in foreign locations far from the spectacular environment of the Pacific Northwest Coast, totem poles have become the cultural ambassadors of First Nations peoples and an icon of Canada. An example is the totem pole in outdoor sculpture garden of Astley Gallery in Uttersberg, Sweden.

"Raven Comes to Uttersberg," Sweden.

Photo: Galleri Astley |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

"Raven, Salmon and Beaver" (above) is by

Don Yeomans, a Haida

Metis artist from BC. He carved the 5.2 meter high pole in 1990 on commission for Astley Gallery, a centre for international art and culture north of Stockholm. The pole was carved from a 360 year old red cedar tree, about 360 from Vancouver Island. Yeomans was commissioned by Stanford University to carve a totem pole in 2002. Entitled "The Stanford Legacy," it chronicles the early death in 1884 of the sole Stanford heir. The pole was carved from a 400 year old cedar, is 12.2 meters high and weighs 4,200 lbs.

The sculpture collection at Stanford University also includes a totem pole by the distinguished Nuu chah nulth artist "Tsaqwassupp" – Art Thompson (1948 – 2003) assisted by John Livingston. Read the tribute to Tsaqwassupp by Taiaiake Alfred:

Art Thompson.

"Boo Qwilla" was carved in 1995 from an ancient red cedar tree and today stands in a grove of trees in front of the School of Business (right). Beside it a plague explains the " Boo Quilla" story: "On this totem pole, Thunderbird, with wings outstretched, towers overhead. He perches on top of Raven, the creator of Earth, Light, and Consciousness. Raven’s wings encompass the headress of Boo Quilla, a person of knowledge, wisdom, and achievement. Legend affirms this ancestral human is Raven's most prized creation who is charged with the safekeeping of knowledge and the preservation of the Earth. At the base, a supernatural Killerwhale transforms into a Wolf. This creature possesses magical healing powers which aid humankind." |

|

"Boo Quilla" by Art Thompson, Stanford.

Photo: Somik Raha |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

The Stanford wealth was made by the railways which opened the West to settlement, leading to the demise of the native population as well as the deforestation of the land. The seal of Stanford University depicts the big tree, "El Palo Alto," Spanish for highest tree (below). This is a living redwood located in Palo Alto, on the corner of the campus. Most of the old growth forests of the Santa Cruz moutains were clearcut by the time of the University's founding in 1891. "El Palo Alto" (right) is a sole survivor, 33.5 meters in height, 2.3 meters in diameter, and over one thousand years old. "El Palo Alto" is a California Historical Landmark, recognized for its significance to the long vanished Coastanoan and Ohlone Indians and as a campsite for the Portola Expedition Party of 1769.

Big tree seal of Stanford University.

Photo: Stanford University |

|

El Palo Alto, Stanford University.

Photo: Postcard, c. 1950

mmmmmmmm |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

©

Credits & Contact |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|