| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Totem Pole Websites |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Totem Poles and Cedar Trees |

|

Dutch Totem Pole Websites |

|

| |

American Totem Pole Websites I |

|

English Totem Pole Websites |

|

| |

American Totem Pole Websites II |

|

Finnish Totem Pole Websites |

|

| |

Australian Totem Pole Websites |

|

German Totem Pole Websites |

|

| |

Austrian Totem Pole Websites |

|

Icelandic Totem Pole Websites |

|

| |

Belgian Totem Pole Websites |

|

Scottish Totem Pole Websites |

|

| |

Canadian Totem Pole Websites I |

|

Swedish Totem Pole Websites |

|

| |

Canadian Totem Pole Websites II |

|

Totem Poles Admired Worldwide |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

American Totem Pole Websites I

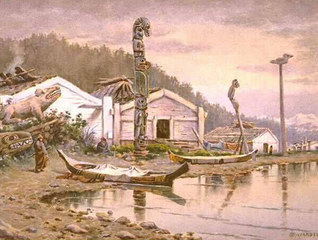

Alaska's Digital Archives

An educational website. Presents historical photographs, albums, oral histories, moving images, maps, documents, physical objects and other resources from ten libraries, museums and archives throughout Alaska. Some 5,000 archival images including many of totem poles and indigenous culture can be browsed online using a searchable database. The database includes the painting by Theodore J. Richardson (1855 – 1914) which depicts traditional Tlingit clan houses and totem poles (right) at Wrangell. From the Rasmuson Library at University of Alaska Fairbanks, the Consortium Library at the University of Alaska Anchorage, and the Alaska State Library in Juneau. |

|

Tlingit Clan House, Wrangell, c. 1915

Painting by T. Richardson |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

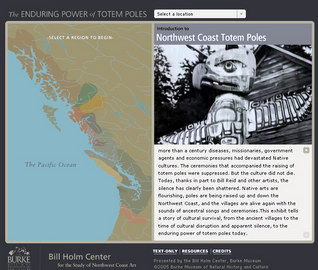

Bill Holm Center

An educational website. Describes a number of projects at the Bill Holm Center for the Study of Northwest Coast Art, established at the Burke Museum in 2003. A founding patron is ethnologist Bill Holm, author of the classic work Northwest Coast Indian Art (1965). A 47 minute video of Bill Holm giving an

illustrated lecture in 2003 at the University of Washington is available online:

Northwest

Coast Indian Art. See the replica sculptures carved by Bill Holm:

Outside

Totem Poles. An example is the Tlingit mortuary pole carved in 1972 from photos of the original which no longer survives

(right). "A chest at the top of the original mortuary pole held the remains of a Tlingit chief. On this replica pole,

the figure of a high ranking man wears a prestigious ringed basketry hat and sits on a carved bentwood chest. The original

pole stood in the village of Old Wrangell (Kasitlan), near present day Wrangell, Alaska. The noted artist Kadyisdu.áxch

probably carved that mortuary pole."

One project initiated by the Center is a totem pole website designed to make archival photos and educational materials on Northwest Coast art available on a searchable database:

The Enduring Power of Totem Poles. See also the resource:

Totem

Pole Bibliography. The carving project by Tlingit artists Stephen and Nathan Jackson is presented:

House Posts. Completed in 2005, the new posts replace two repatriated grizzly bear posts which were returned in 2001 to the Cape Fox Corporation. Another page is devoted to a carving taken in 1899 and its repatriation to the Taantakwaan people:

Tongass Sea Lion. One page describes a project by enthnologist Robin K. Wright:

Haida House Models. It features 29 models that are replicas of Haida houses at Skidegate. The house models were commissioned for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

An early photo of Bill Holm shows him helping to raise the Mungo Martin memorial pole at 'Yalis in 1970. Carved by Tony Hunt, it was the first to be raised here in 40 years. See:

Wesley Wehr Guide. From the University of Washington and Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. |

|

Tlingit mortuary pole replica.

Photo: University of Washington

Bill Holmes (right), 'Yalis, 1970.

Photo: Wesley Wehr |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Boo-Qwilla

Totem Pole

An educational website. One page is a virtual field trip of the outdoor sculpture collection on the campus of Stanford University in California. Includes a map, descriptions of each sculpture and illustrations by the middle school students. One girl depicted Boo – Qwilla, a totem pole carved by the the highly respected Dididaht artist Art Thompson from Vancouver Island (right). She records her personal reaction to the aboriginal sculpture: "When I first viewed the piece, I was in awe of the excellent craftsmanship of a sculpture which relates legends of the Northwest Coast Americans." From Jordan Middle School, Palo Alto, California. |

|

Boo-qwila by Art Thompson (detail).

Stanford University, California |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

British Columbia,

Alaska and Yukon Totems

A commercial website. Includes three galleries each with fifteen photos of totem poles in British Columbia, Alaska and the Yukon. Close up photos reveal the weathered condition of the cedar (right). Among the totem poles featured are those at the Civic Center of Prince Rupert (BC); Saxman Totem Pole Park, Chief Shakes Island, Auke Bay Recreation Area Juneau; Juneau Douglas Museum; Wrangell Totem Pole Park; the Sitka National Historic Park; Raven's Fort Tribal House at Haines; and the Friendship Totem Pole by Yukon River at Whitehorse. From Image West Photography. |

|

Haida totem pole, Prince Rupert (detail).

Photo: Image West |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Cape Fox Village Totem Poles

No longer online. A commercial website. One page documents the removal of a Teikweidi totem pole from the Tlingit village of Gaash at Cape Fox by the Harriman Expedition in 1899. Describes the 1999 repatriation petition by the descendants of the Tlingit Saanya Kwaan tribe to the Peabody Museum at Harvard University. Cape Fox Corporation initiated the repatriation project for the Tlingit clans at Saxman: Teikweidi (Brown Bear), Neix.adi (Eagle – Beaver – Halibut) and Kiks – adi (Frog). The Teikweidi clan gave the Peabody Museum at Harvard University a large red cedar in appreciation for returning the pole which portrayed a bear peering from its den. A replacement pole was carved by Nathan Jackson, a Tlingit carver from Ketchikan. Includes archival photos and a gallery of the pole raising.

The Seattle photographer Edward S. Curtis was a member of the 1899 Harriman Alaska Expedition and he documented the "deserted" Cape Fox Village for a souvenir album (right). In 2001, eight totem poles and house posts looted by the Harriman Expedition were returned to Cape Fox from the five institutions that held them, including the Field Museum in Chicago, the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian, Harvard's Peabody Museum and the Burke Museum in Seattle. External links:

A

Totem Pole Comes Home (Harvard Gazette, 2001); and:

Tlingit History Heads Home (Sealaska Heritage Institute). From the Cape Fox Corporation. Note: this is a First Nations owned site. |

|

"Deserted Chief's House," Cape Fox, 1899.

Edward S. Curtis

"A Household God – Deserted Village," 1899.

Edward S. Curtis |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Chief

Shakes Island

A commercial website. Presents the fascinating history of Chief Shakes Tribal House which is in the middle of Wrangell Harbour. Excerpts are from a pamphlet by E. L. Keithan, printed in 1940 by the Wrangell Sentinel. The Tribal House was rehabilitated in 1939 under a Civilian Conservation Corps program and is on the National Register as an historic monument. "The title of 'Shakes,' or as it is originally known, 'We Shakes,' was originally conferred upon Chief Gushklin of the Stikine Nan yan yi Tlingit settlement near present day Wrangell after a victory in war against the Niska Indians of BC. The Niska Chief We Shakes, rather than submit to the degradation of being a slave to the victorious Tlingit Chief removed his 'killer whale' hat and placed it on Gushklin's head, giving him his own name 'We Shakes.' For reasons unknown, the name has since been shortened to 'Shakes.'

Chief Shakes House shows "the impressive architecture of a house of high caste among the Tlingit natives. The doorway shows a figure with many faces. Natives believed that each part of the body could act independent of another, so eyes were placed at joints to depict the power and spirit allowing independent action. Carved replicas of the Shakes Clan houseposts adorn the interior of the structure. The original houseposts, over 200 years old, can be viewed in the Museum, on loan from the Wrangell Cooperative Association." From the City of Wrangell. |

|

Chief Shakes House.

Wrangell, Alaska |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Conservation of

Northwest Coast Totem Poles

A personal website. One page is an academic paper by Charles Rhyne on totem poles published in "Zeitschrift fuer Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung" (2003). He says: "Totem poles are recognized as one of the great monumental forms in the history of art, comparable in stature and in the intensity of meaning to Egyptian cenotaphs, Roman triumphal columns, and Mayan stele. . . Today, they are increasingly commissioned and installed by non native businesses and governments around the world. They provide rich evidence for understanding the complex interplay of the values and approaches to the conservation of all historical and artistic works." Includes a paper on the "rethinking of conservation theory and practice worldwide" presented in 2000:

Changing Approaches. Rhyne writes: "In recent years organizations such as UNESCO have begun to recognize 'intangible heritage,' significantly expanding Euro American concepts of cultural heritage and giving voice to previously marginalized peoples."

Charles Rhyne wrote Expanding the Circle (1998), a book on "guud san glans" (Eagle of the Dawn), Robert Davidson. The Haida artist is quoted: "Since the almost complete destruction of our spirit, the disconnection of our values and beliefs, it has been the art that has brought us back to our roots." His work "Breaking the Totem Barrier" (right) is pictured on the cover. From Charles S. Rhyne, Professor Emeritus of Art History, Reed College. |

|

"Breaking the Totem Barrier," 1989.

Totem pole by Robert Davidson |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

The Changing Meanings of a Totem Pole

A personal website. One page is an ethnohistory paper by Frederic Gleach on the looting of an uninhabited Tlingit village at Cape Fox in July 1899 by the Harriman Alaska Expedition: "From Cape Fox, Alaska to Cornell University: The changing meanings of a totem pole." Many of the looted artifacts were dispersed to public and private collections across the US, such as the totem pole that ended up in the collection of Cornell University (right). Gleach explains that these artifacts have two cultural meanings: to the Cape Fox Tlingits; and to the Anglo American academic community.

Gleach writes: "The removal of cultural works from Alaska to established American centers of learning and commerce demonstrated US possession and the right to dominate, the control over territory, people, and culture obtained and asserted by the Alaska Purchase." In 1899 Cornell had no anthropology department and 25 years later the pole was put in storage where it languished until 2001 when it was repatriated as part of the revival of the Harriman Expedition. From Frederic Gleach. |

|

Tlingit pole, 1911.

Cornell University, New York State |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

David Boxley Totems

A commercial website. Markets the carving and totem poles by Tsimshian artist David Boxley (b. 1952) from Metlakatla, Alaska (right). "Totem poles were created and raised to represent a family clan, its kinship system, its dignity, its accomplishments, it prestige, its adventures, its stories, its rights and prerogatives. A totem pole served, in essence, as the emblem of a family or clan and often as a reminder of its ancestry." Three gallery pages show some of the 65 totem poles the artist has carved in the last 26 years, many of them on public display. From David Boxley. |

|

Tsimshian carver David Boxley.

Metlakatla, Alaska |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

DeMenil Totem Pole Photos

An educational website. One page functions as a searchable research tool for some 20,000 images of totem poles donated to the Burke Museum in 2001 by photographer Adelaide DeMenil. The photos can be browsed in 35 galleries of Haida, Tlingit, Kwakwaka'wakw and Tsimshian totem poles organized by location; from Alert Bay and Bella Bella in British Columbia, to Wrangel in Alaska. Includes photos of totem poles in the George Thornton Emmons Collection and the Viola Garfield Collection. From University of Washington and the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. |

|

Turnour Island, BC, 1967.

Photo: Adelaide DeMenil |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Early Totem

Carvers of New Metlakatla

A personal website. A scholarly presentation of Northwest Coast art with a focus on the carvers of New Metlakatla, Alaska. The village was founded in 1887 by a church minister and 830 Tshimsian followers. "In their Canadian homeland, the Tsimshians had been the carvers of huge house poles, dance screens, and ceremonial objects of all kinds, in an artistic tradition extending back hundreds if not thousands of years. This came to an end in New Metlakatla, and for many years only small souvenir items were carved for the tourist trade; with little if any sign of the traditional style. Though they are evidence of the loss of a great artistic tradition, these small poles represent a victory too; that they were made at all then, and still exist now. And the descendants of the carvers have returned to the art of the past, and have both learned and recreated the traditional style, and brought it into the 20th and 21st centuries."

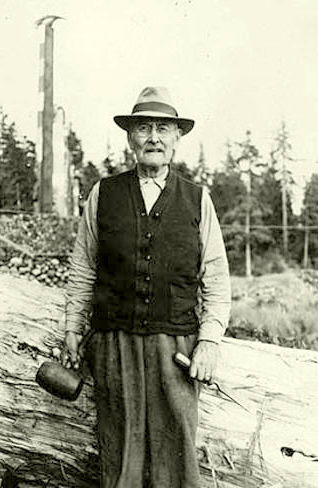

Presents archival photos and biographical notes on the Tsimshian carvers Eli Tait, Sydney Campbell,

Clyde Boyd, Roy Bolton and Casper Mather (1876 – 1972), who is pictured on the right in a tourist postcard published in 1940. See:

Biographies.

Describes the mysterious "friendship" carving:

Good Luck Totem.

Another page features the carvers of the Blunden Harbor – Smith Inlet area in British Columbia that includes the House of Walkius in 'Yalis (Alert Bay) where the seminal Kwickwaineuk woman carver Ellen Neel was born:

Kwakiutl

Carvers. From Steve Akerman. |

|

Carvings by Eli Tait and Casper Mather.

Photo: Steve Akerman

Tsimshian carver Casper Mather, 1940.

Photo: Otto Schallerer |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Enduring Power of Totem Poles

An educational website. This stunning new website was launched in September 2008. It provides an interactive map of the Northwest Coast (right) and is a comprehensive presentation with videos and text of the cultural and geographic range of the art of totem pole carving. The website originated with the 2003 exhibit at the Burke Museum entitled "Out of the Silence: The Enduring Power of Totem Poles." The exhibit had been inspired by the book Out of the Silence, written by Bill Reid in 1970 and illustrated by the photographs of Adelaide de Menil. The website is funded by the National Endowment for the Arts and the Quest For Truth Foundation. From the University of Washington and Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. |

|

Enduring Power of Totem Poles, 2008.

Website homepage, Washington University |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Founders' Totem Pole

No longer online. A commercial website. One page documents the carving of a Tlingit style totem pole on 29 August 2001 to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the Pilchuck Glass School. The carving of the "Founders' Totem Pole" began in the Alaska Indian Arts studio in Haines, Alaska and was later moved to the Pilchuck Glass School in Washington State where some elements were cast in glass. The main carver was John Hagen (right). Assistants were Wayne Price, David Svenson, Greg Horner and Clifford Thomas. A documentary film about the pole was screened at the Seattle Art Museum on 25 January 2008. From the Pilchuck Glass School. |

|

Carver John Hagen, Founders' Pole, 2001.

Photo: Russell Johnson |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Fred Jones British Columbian Totem Poles

No longer online. A commercial website. One page is a general history of totem poles based on seconday sources. The Fred Jones totem poles from BC are displayed at the entrance to the Red Earth Museum in Oklahoma City. There is no information about the totem poles or how they came into the hands of Fred Jones. From Red Earth Inc. |

|

Gitksan totem pole, Gitanyow.

British Columbia |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Gitksan Totems

A commercial website. Includes a gallery page of totem poles photographed in the Gitksan communities of Gitanyow (right) and Gitwangak in British Columbia. External link with a map of the area:

Skeena Buckley River First Nations

(Northwest Tribal Treaty Nations). Gitanyow, Gitwangak, Kispiox, Glen Vowell and Gitanmaax are represented by hereditary and

elected Gitksan leaders. External links:

Gitxsan Chief's Office and

Gitksan Government Commission.

A second gallery page of totem poles displayed in Ketchikan, Alaska is presented:

Saxman Village.

A third gallery page presents photographs taken at the Sitka National Historical Park:

Tlingit Totems.

From Adventure Learning Foundation. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Heraldic

Columns of the Northwest Coast

An educational website. Presents a scholarly essay by the ethnologist and Burke Museum director Robin K. Wright. He describes totem poles as "heraldic columns" and considers the folk traditions of this art form and how it was impacted by western influences: "Gyáa'aang is the Haida language word for the tall red cedar poles carved with images from family histories on the northern Northwest Coast. . . The term 'totem pole' is not a native Northwest Coast phrase. In fact, the use of the term 'totem' to refer to the Northwest Coast images of family crests or emblems is not strictly accurate." From the University of Washington. |

|

Totem poles, Howkan, Alaska, c. 1900.

Photo: University of Washington |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

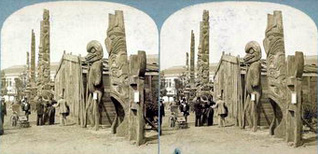

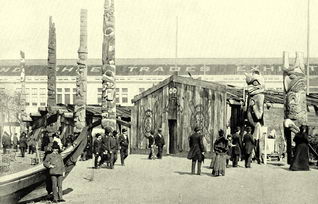

Totem poles and Northwest Coast art and culture were first introduced in a popular context to the American public at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. A stereoscopic postcard of monumental Kwakwaka'wakw and Haida carvings is derogatorily entitled "Idols of the British Columbia Indians" (right). The guide stated it was "a real camp or village of the Quackuhl Indians, with these same totem poles in their actual condition, as brought from the Northwest"

Totem

Poles (The Dream City, 1894).

A second view (right) shows the painted facade of the Kwakwaka'wakw house which came from Tsaxis (Fort Rupert). Working together with ethnologist Franz Boas, Kwakiutl George Hunt helped to acquire a large and varied collection of totem poles and other ethnographic artifacts. These objects were sent to Chicago along with 15 Kwakiutl adults and two children who appeared in the exhibit; "Here the groups of Native American peoples were to be arranged geographically, and to live under normal conditions in their natural habitations during the six months of the Exposition" (A History of the World's Columbian Exposition, 1898). Following the end of the Exposition in 1893, the totem poles were purchased by the Field Museum in Chicago. Whether the First Nations received an equitable price for these monumental works is not known, but the loss of cultural heritage was devasting to the native communities. |

|

Kwakiutl poles, Chicago, 1893.

Photo: World's Columbia Exposition

"Idols of the British Columbian Indians."

Stereoscopic Views |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Hydaburg Pole Raising

An educational website. Commemorates a pole raising on 23 July 2003 to celebrate the lifetime achievements of respected Haida elder Woodrow W. Morrison. "Woody" was born on 3 February 1913, the first child born in the new consolidated village of Hydaburg on the Prince of Wales Island in Alaska. One of the few Haida elders to be a fluent speaker of the Haida language, Woody was a resident of Hydaburg during Alaska's years as a possession, a territory and a state." Read:

Citation. From the Sealaska Heritage Institute. Note: this is a First Nations owned site. |

|

Pole raising, Hydaburg, 2003.

Photo: Sealaska Heritage Institute |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

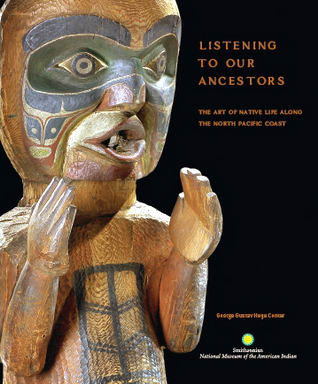

Hydaburg Totem Park

A governmental website. Presents the Hydaburg Totem Park in the Tongass National Forest, Alaska, which was founded in 1939 as a National Historic Site "to preserve the totemic art of Pacific Northwest Coast Haida people." The Hydaburg Indian Reservation was established in 1911 and Haida people from three villages were consolidated here. In the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps and the US Forest Service brought 21 totem poles to Hydaburg, five of which were restored. The remaining 16 poles were replicated between 1939 and 1942 under the direction of Haida master carver John Wallace (right). Previously he had carved two poles commissioned by the Secretary of the Interior for the Dept. of the Interior in Washington, DC.

"The park represents a unique cooperative effort among the Federal government, local officials and native Alaskans to recognize and protect local Alaskan culture, and enhance tourism. The works of art in the park are associated with longstanding native traditions. Oral histories indicate that the carving of poles, monuments and houseposts is an ancient tradition among the Haida. The totem poles represent the people, their stories and their history. The figures carved on the poles generally represent ancestors and supernatural beings once encountered by them." From the US National Park Service. |

|

Haida carver John Wallace, 1940.

Photo: University of Washington |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Kasaan Totem Pole Project

No longer online. A governmental website. One page presents a gallery of photos showing the early stages of the first totem pole project in Kasaan, Alaska in over fifty years. The pole was carved by Tsimshian artist Stan Marsden (right). A gallery on the website of the Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska shows 300 photos of the totem pole raising and traditional celebrations on 15 September 2007. One hundred years earlier, in 1907, Old Kassan had been established as a National Monument to preserve the totem poles and community houses in the deserted village. Related link:

Kassaan Totem Pole Raising.

A second page on the main website describes the history of totem poles: "During the early part of the 20th century, the carvers in Kasaan produced poles that were placed in Saxman, Ketchikan, and Sitka; and long before that, incredible pieces of monumental artwork decorated Old Kasaan and were traded along the Northwest coast. The beaches of Old Kasaan were undoubtedly Haida, and showed a b tradition with some of the finest totem poles and clan houses. The cultural landscape of Kasaan has changed, though, as it has in all Haida communities."

"At one time, there were at least 24 Haida villages, with four of them on Prince of Wales Island. Adverse living conditions forced these villages to consolidate or migrate, and Old Kasaan, Howkan, Sukkwan and Klinkwan collectively became Kasaan and Hydaburg. From around 1920 on, cultural activities receded, especially in language learning and the carving of monumental items like clan houses, totem poles, and sea going dugout canoes."

"These things happened because the Haida people were experiencing near extinction, as population numbers dropped from 70 – 90 percent within their villages due to foreign illnesses and food shortages. It was a dark time for the Haida people, but once again, that landscape is changing, as Kasaan begins its first totem pole in modern history." From the Organized Village of Kasaan. Note: this is a First Nations owned site. |

|

Carver Stan Marsden, 2006.

Photo: Organized Village of Kasaan

Traditional house post, 2007.

Organized Village of Kasaan |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Totem poles at Old Kasaan, c. 1900.

Photo: University of Washington

Also in the 1930s the American Civilian Conservation Corps and the US Forest Service initiated a project to remove the surviving totem poles and grave sculptures from the old native village sites on the Northwest Coast. These were brought to Kasaan, Sitka, Ketchikan and Wrangell where native carvers were employed to restore the old totem poles and make replicas for new tourist orientated totem parks.

Whale Memorial, Old Kasaan, 1898.

Photo: Alaska's Digital Archives |

|

Old Kasaan was located on the Prince of Wales Island in Alaska. When it was

photographed in 1900, it was a Kaigani Haida village with many still standing monumental totem poles (left). Like most indigenous

villages on the Northwest Coast, the village and its burial grounds were plundered by collectors. In the 1930s, the Haida villages were "consolidated" by the government and relocated; Old Kasaan, Howkan, Sukkwan and Klinkwan collectively became Hydaburg and Kasaan.

Whale Memorial, Old Kasaan, 1940.

Photo: Alaska's Digital Archives

A Killer Whale totem on top of a grave house at Old Kassan was photographed in 1898 (left). An archival note identifies it as Chief Skowl's grave, at Skowl Arm, Kasaan Bay. Some 40 years later the chief's memorial is seen fallen to the ground observed by a young native boy (above). A similar whale monument from Howkan "Single Fin," carved c. 1880 by the Haida artist John Wallace, was replicated by the non native carver Bill Holm and is displayed today in front of the Burke Museum in Seattle. See:

Outside

Totem Poles. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Klawock

Totem Pole Raising

A commercial website. Presents a photo gallery of seven Tlingit totem poles being raised at the Totem Park in Klawock on the Prince of Wales Island in Alaska. The last of the seven was a Raven Clan totem pole (right) by carver Jon Rowan. The totem poles were raised over a three day period in 2005. Related link:

Klawock

Raises Seven Poles (Sealaska Heritage). The Totem Park was set up in the 1930s when the Civilian Conservation Corps and the US Forest Service removed the old totem poles from the village of Tuxekan and brought them to Klawock where native carvers restored them and made replicas. From Prince of Wales Online. |

|

Klawock totem pole raising, 2005.

Photo: Seaheritage |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

"Early inhabitants were from Tuxekan, a Tlingit winter village to the north. Klawock was used as a summer fishing camp, and has been known as Klawerak, Tlevak, Clevak, and Klawak. The history of Klawock is closely tied to the fishing industry. A trading post and salmon saltery were established in 1868, and the first cannery in Alaska was built here by a San Francisco firm in 1878. Between 1897 and 1917 a salmon hatchery for red salmon operated at Klawock Lake. Two more canneries opened in 1920 and 1924. . . In 1912 Klawock residents established the Alaska Native Brotherhood and Alaska Native Sisterhood as non profit organizations . . . The City recently built a Long House and a new Totem Pole was raised at that site in 1998. Native organizations are Klawock Heenya Corporation and Klawock Cooperative Association" City of Klawock. |

|

Totem pole raising, 2005.

Klawock, Alaska |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Klukwan House Posts

No longer online. A commercial website. Markets the work of Tlingit carver Frank Fulmer. Also presents the four house posts of the masterwork known as the Whale House of Klukwan (right). "They were created in the 18th century by a famous Tlingit carver named 'The One Who is Listened To.' Whom I would consider to be the 'Michelangelo Buonarroti' of his era, he was light years ahead of his time. The house posts are excellent examples of how Tlingit Indians record their stories using hieroglyphic art. Four houseposts were used inside a traditional long house to support the main roof structure. This allowed guest who entered the long house to see and read the clan house stories."

A summary of the ancient Tlingit legend behind each house post is presented; Raven and Bullhead (left); Chief's Daughter (far left); Konakadet; and Duk Toothl. Frank Fulmer was inspired to be an artist by his great grandfather, Frank St. Clair, who was a carver. "One of his totem poles stands in front of Juneau Governor's Mansion and a second totem the Yax – Te pole stands in Auke Bay. It is an honor to follow in the foot steps of my Ancestors. Through my works of art, I strive to bring Honor and Glory to who we are Shuka'. . . The generations who have paved the way before me and the generations to follow." From Frank Fulmer. Note: this is a First Nations owned site. |

|

Whale House Posts, Klukwan.

Photos: A. DeMenil |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Klukwan

Whale House

An educational website. Features a fascinating story about one of the greatest works of Northwest Coast art; the Tlingit Whale House of Klukwan. Presents articles and photos from the "Whale House Series" published by the Anchorage Daily News in five sections:

Part I -

The Sale of the Whale House Legacy;

Part II -

The Carving the Masterworks;

Part III – A Tlingit Buyer of Tlingit Artifacts;

Part IV – A Dealer's Passion for the Whale House;

Part V – An Epic Saga Becomes Litigation. Provides the 1993 legal decision on "the conversion of tribal trust property and violation of a tribal ordinance which prohibits the removal of such property from the village without prior notification of and approval." See:

Chilkat Indian Village.

The contents of the Whale House were removed in 1984 by a Seattle art dealer who wanted to sell them to Adelaide DeMenil, a wealthy New York photographer whose husband was the anthropologist Edmund Carpenter. The post (right) tells of an event that "took place in a village long before the Ganaxteidi moved north to Klukwan. The human figure at the top of the post represents Dukt'ootl', Black Skin, symbolizes the rock island on the west coast of Prince of Wales Island. . . The sea lion forms the central figure. His protruding tongue represents death as the body is split in half. The sea lion's fore flippers are carved parallel with the body under the man's forearms and the back flippers are shown in front of his shoulders." Research was sponsored by Alaska Federation of Natives, University of Alaska, National Science Foundation and Alaska Department of Education. From Alaska Native Knowledge Network. Note: this is a First Nations owned site. |

|

Whale House Posts, Klukwan.

Photos: A. DeMenil |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

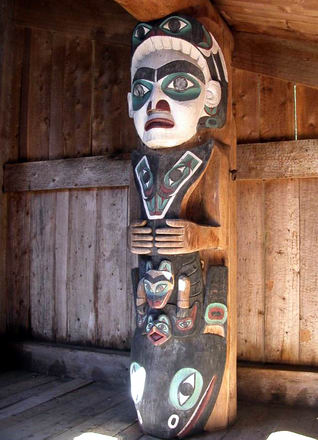

Listening To Our Ancestors

An educational website. Presents an exhibition of more than 400 museum objects, most of them carved from cedar, that show: "The Art of Native Life along the North Pacific Coast." Organized by the National Museum of the American Indian the exhibit opened in Washington DC in 2006, then traveled to the George Gustav Heyne Center in New York. In 2008 a core collection of objects will to travel to the 11 native communities from which they originated: the Coast Salish, Makah, Nuu chah nulth, Kwakwaka'wakw, Heiltsuk, Nuxalk, Tsimshian, Nisga'a, Gitxsan, Haida and Tlingit.

The exhibit centrepiece, a 19th century Kwakwaka'wakw welcome figure carved in red cedar, appears on the cover of the accompanying book and Kwakwaka'wakw Chief Robert Joseph is an curatorial advisor. First Nations representatives discuss the ways in which the objects on display "connect them with their forebears and enrich their world today." Zoomable photos of the objects, described as "masterpieces of art" from "unique nations" make the presentation especially vivid. From the Smithsonian Institution. |

|

"Listening To Our Ancestors," 2007.

Photo: Smithsonian Institution |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Lumni Healing Poles

No longer online. A commercial website. Markets the "Healing Poles" created by Jewell Praying Wolf James. Presents a description by the carver, a photo gallery, the journey map and press archives. Lummi carvers made a healing pole memorial to help America share its grief after the 2001 terrorist attacks. The carvers transported the pole across the US with ceremonial stops seek healing prayers, blessings and songs of elders from 25 tribes. It arrived in Washington in 2003 (right). From Kurt Russo. |

|

Lummi Healing Pole, Washington DC, 2003.

Photo: Kurt Russo |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Monuments in Cedar

An educational website. Presents the documentary book "Monuments in Cedar: The Authentic

Story of the Totem Pole" by Edward Keithahn, first published in 1945. The author was the long time director of the Alaska Museum, a member of the American Anthropological Society and a Fellow of the American Association for Advancement of Science. He saw his first totem pole clusters in their original location in First Nations villages at Bella Bella, Alert Bay and Ketchikan. Inspired by the poles, in 1928 Keithahn moved to the "Totempolar Region" to do research. He identified six types of poles: house pillar and false house pillar, mortuary, memorial, potlatch, ridicule and heraldic. The monumental poles photographed at the incorrectly identified as deserted Tlingit village of Gaash served a heraldic purpose (right).

Keithahn ended his chapter "Totem Pole Restoration" with the words: "The time is not far distant when these monuments will be considered a resource as important to Southeastern Alaska and Coastal British Columbia as the pyramids are to Egypt or the ruins of ancient Rome to modern Italy. The significant fact is simply that no other place in the whole world has totempoles; people will come from far and wide to see them . . . as long as they remain." From the University of Alaska at Anchorage.

The Sun and Raven Totem Pole was carved in 1902 by the famous Tlingit carver, Kaahctan (also known as Nawiski), for a woman of the Starfish House of the Raven Clan, as a memorial to her two sons (right). It was placed in the Tlingit cemetery on Pennock Island facing Ketchikan. The mortuary pole was removed and restored and on 11 April 1939 became the first pole in Saxman Totem Park (far right).

In 1996 Tlingit carver Israel Shotridge carved a 10 foot replica of the Sun and Raven Totem Pole which today stands in Garrison, New York. See:

Shotridge Studios. |

|

"Deserted Village," (Cape Fox) 1899.

Edward S. Curtis

Tlingit Sun and Raven Pole.

Alaska Digital Archives |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Northwest

Coast Native Art and Culture

A commercial website. One page presents a book entitled "The Forest Lover" by Susan Vreeland. The book is about the artist Emily Carr (1871 – 1945) who painted totem poles, such as those at Tanoo (right). Her work expressed her belief that "The oldest art of our West, the art of the Indians, is in spirit very modern, full of liveliness and vitality." Vreeland remarks that as a settler, "Emily was painfully conscious of the thin line between appreciation and appropriation. At times, she must have felt overwhelmed by mysteries beyond her grasp." From Susan Vreeland. |

|

Haida village and totem poles at Tanoo.

Painting by Emily Carr, 1913 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Out

Of the Silence

An educational website. One page presents the exhibit "Out of the Silence: the Enduring Power of Totem Poles" held in 2002 at the Burke Museum. Features the photographs by Adelaide DeMenil who together with Haida artist Bill Reid researched the totem poles that were fast "disappearing" from their original locations in First Nations communities on the Northwest Coast in the 1960s (right). DeMenil and Reid published their research in 1971 as a book.

Like the book, the 2002 exhibition affirmed the resurgence of indigenous cultures and celebrated the close connection between Northwest Coast carving traditions and community identities. Clearly both the art of totem pole carving and the repatriation of totem poles have brought about a new recognition of the meaning and value of this monumental art form. From the University of Washington and the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. |

|

Heiltsuk totem pole (detail), 1967.

Photo: Adelaide DeMenil |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

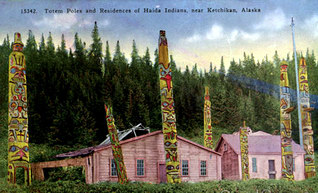

Present

at Creation: Totem Poles

An educational website. One in a series on National Public Radio called "Exploring Icons of American Culture." Provides several audio interviews: by Robert Smith (30 September 2002) on the revival of the art of carving totem poles and as generic symbols of Native American culture; by Elizabeth Arnold (1989) on the 1899 pillaging of totem poles by railroad baron Edward Harriman; and by Anne Sutton (July 2001) on the descendants of the Tlingit Tribe celebrating the return of the totem poles. From National Public Radio. |

|

Totem poles and residences of Haida Indians.

Old postcard from Ketchikan, Alaska |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

©

Credits & Contact |

|

| |

|

|

|

|