|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Cathedral Grove, British Columbia |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Our Big Tree Heritage |

|

Ancient Forest Extermination |

|

| |

Linking Two Biospheres |

|

Protecting Park Values |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

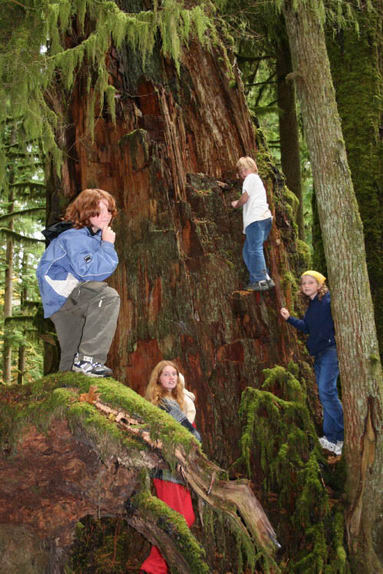

Our Big Tree Heritage

The big tree heritage that belongs to human beings everywhere

in the world is vanishing as old growth forests are increasingly demolished

by the logging industry. Cathedral Grove on Vancouver Island in British Columbia

(BC) is a rare and endangered remnant of a coastal Douglas fir ecosystem (right).

The biggest trees here are about 800 years old and measure some 75 m (250 ft)

in height and 9 m (29 ft) in circumference. They are the survivors of a forest

fire that ravaged the area some 350 years ago and the even more devastating

invasion by Europeans who colonized Vancouver Island from 1849. Although spiritual

in meaning, "Cathedral Grove" is a name embedded in a romantic and

Eurocentric attitude toward nature that does not adequately respect the stewardship

of the Indigenous Peoples. |

|

Dutch children visiting Cathedral Grove.

Photo: Eugeni Piepenbroek |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

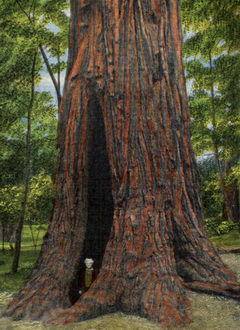

Bark stripped cedar, Cathedral Grove, 2004.

Photo: Ingmar Lee

The ancient red cedar (Thuja plicata) specimen that survives

in Cathedral Grove (right) represents a critical species to Indigenous identity

and culture on the Northwest Coast. The way of life of these Indigenous or

Aboriginal Peoples, known in Canada as First Nations, is dependent on cedar,

with which they have a complex and rich relationship: "For

thousands of years these people developed the tools and technologies to fell

the giant cedars that grew in profusion. They used the rot resistant wood for

graceful dugout canoes to travel the coastal waters, massive post and beam

houses in which to live, steambent boxes for storage, monumental carved poles

to declare their lineage and dramatic dance masks to evoke the spirit world.

Every part of the cedar had a use. The versatile inner bark they wove into

intricately patterned mats and baskets, plied into rope and processed to make

the soft, warm, yet water repellent clothing so well suited to the raincoast.

Tough but flexible withes made lashing and heavy duty rope. The roots they

wove into watertight baskets embellished with strong designs. For all these

gifts, the Northwest Coast peoples held the cedar and its spirit in high regard,

believing deeply in its healing and spiritual powers. Respectfully, they addressed

the cedar as Long Life Maker, Life Giver and Healing Woman." In Hillary

Stewart, 'Cedar, Tree of Life to the Northwest Coast Indians' (1985). |

|

Indigenous Heritage Trees Indigenous peoples have modified trees in BC as part of their traditional use of the forest. Not far from the giant Douglas firs in the heart of Cathedral Grove are unprotected archaeological artifacts. These "culturally modified trees" are red cedars that have had their bark stripped off for aboriginal and ceremonial purposes (left). They are unique signposts of indigenous occupation and provide evidence of Aboriginal Title and Rights: some have been dated back to 1137 AD. Yet such trees have no legal protection due to an ineffectual provincial "smoke screen" Heritage Conservation Act.

Ancient cedar, Cathedral Grove.

Photo: Carol Ann Fuegi |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Museum of Anthropology, Vancouver.

University of British Columbia

Totem

Poles and Cedar Trees Without an abundance of old growth cedar resources,

the Northwest Coast art forms, of which totem poles are the most monumental,

will collapse. Totem poles are a political manifestation of pre-colony sovereign

Indigenous identity. Union of BC Indian Chiefs: "Before colonization,

First Nations were self governing, self sustaining nations, with legal, administrative

and diplomatic systems that owned and managed their lands and resource. Relationship

patterns changed dramatically, however, when a colonial European infrastructure

was established and settlement by Europeans and Americans was promoted." Ancient

cedar trees are evidence of how First Nations have managed nature sustainably

for thousands of years. Right: a giant cedar tree, bark stripped perhaps a

hundred years ago by members of the Nuxalk Nation (Bella Coola Indians). This

giant cedar tree stands in an ancient grove in the Bella Coola Valley and is

visited by thousands of non native tourists every year who are fascinated by

its Indigenous (Nuxalk) identity. |

|

Totem Poles Admired Worldwide First Nations culture as expressed in monumental cedar carvings is celebrated worldwide. The Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver is renowned for its outstanding collection (left). Such recognition has not slowed the relentless destruction of the forests by the logging industry which followed the invasion by Europeans. Not only did it result in the desecration of "totem" trees, but also in great suffering by the Indigenous communities.

Child visiting a Nuxalk heritage tree.

Bella Coola Valley, Nuxalk Territory |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Ancient cedar tree, Cathedral Grove, 2005.

Photo: Phil Carson

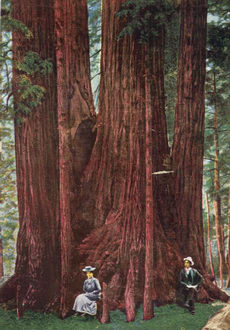

Cathedral Grove, Muir Woods.

Marin County, California |

|

Big Trees as Cathedrals of Nature Groves of ancient trees are today rare everywhere in the world. Visiting a cedar matriarch in Cathedral Grove is an inspiring experience (left). Such ancient groves are treasures of biodiversity that compare in value to European cathedrals. Arboreal groves resemble Gothic cathedrals with their ribbed upward striving vaults, naves, transepts and choirs. This sylvan architectural origin is embodied in Chartres Cathedral (below). The sacred cathedral site was first inhabited by an ancient oak grove where Druids held their ceremonies. A Christian church was erected here n in the fourth century which remained until the cathedral construction began in 1194. Celebrated as the epitome of the Gothic era, Chartres Cathedral is no older than the big tree groves in BC today at risk of extermination.

Gothic pillars and naves.

Chartres Cathedral, France

Ancient tree stands in North America, such as the redwoods

in Muir Woods (right), are ecosystems dominated by gigantic trees of an age

far predating colonization by Europeans. The big trees in Cathedral Grove

belong to a rare forest remnant of the Douglas fir habitat that has been

decimated by industrial logging. No scientific evidence exists that such

forests, once destroyed, can readily regrow, and even regenerated forests

would take centuries to mature. The trees of Cathedral Grove form a

multiple treetop canopy similar to the ceiling of a cathedral (below). |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Douglas firs, Cathedral Grove.

Photo: Eric Ruendal |

|

"Cathedral Grove," 2005.

Painting by Diane Rae

Beams of natural sunlight filter down from the canopy

of Cathedral Grove (left), giving an impression of being inside the nave of

a church. About her painting (above), Diane Rae says "The similarity between

the interior of Chartres Cathedral and an old growth forest is revealed by

the great stature of rounded form which reaches upward towards the light, spilling

into filtered patterns throughout the damp space and inspiring a sense of awe

at the enfolding grandeur of the scene" |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Not many of the ancient redwood groves in California

were saved from the ravages of the logging industry. It was only due to the

dedicated effort by conservationists that some of the big trees are still standing

today to remind people of the magnificent rainforest habitat which not long

ago covered the West Coast of North America.

Right: Old postcard of

a couple sitting on the massive gnarled base of the "Cathedral Tree" in

the Big Trees Grove at Felton, Santa Cruz County, California, 1903. Now part

of the Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park.

Left: Old postcard of a

person peaking out from a hollow in the 326 ft high redwood called "Mother Tree" in

the Big Trees Grove at Big Basin Park, Santa Cruz County. Founded in 1902,

this is California's oldest state park. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Trees as Individuals In Europe monumental and exceptional trees are fully protected as natural heritage, or nature monuments and numerous websites are dedicated to big trees which are in many instances given names. Yet most of these trees are no more than 500 years old and rarely reach over 800 years. By contrast, in BC the age of ancient trees may be much greater, up to 2000 years in some cases, yet they have no protection from the industrial onslaught.

Ancient Douglas fir tree, Cathedral Grove.

Vancouver Island, British Columbia |

|

Tourist and Douglas fir tree, Cathedral Grove.

Vancouver Island, British Columbia

Friends of Cathedral Grove (FROG) Due to ineffectual park management, the grassroots group was formed to protect the nearly extirpated Douglas fir ecosystem of Cathedral Grove (left). "Amongst the worst of the numerous ecological tragedies that have been wreaked on this diverse forest over the past 150 years has been the near total extermination of primaeval Douglas fir. Now more than 97 percent of this once magnificent forest is gone, and to add insult to injury, the industry has cut its way through the subsequent forest profile down to the 30 year old pecker poles which one sees everywhere being shipped south, across the border so Americans can run them through their mills" Ingmar Lee. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Big

Trees as Natural Monuments Big tree expert and biologist Al Carder published

his second book on giant trees in 2005 (right). He states that the 800 year old

Douglas firs in Cathedral Grove do not even qualify as "big trees" compared

to what he saw as a youth on the BC mainland. Born in 1912 in Vancouver, Carder

remembers the Fraser Valley — where today an urban metropolis sprawls — when

many of the spectacular ancient groves of Douglas fir were still standing, some

with awesome trees well over 122 m (400 ft) tall. He explains that because these

mammoths were too large to be easily felled, transported and milled, they were

usually left intact where they were standing. This changed when industrial technology

advanced in the 1940s, following WW2. Carder makes the point that

native trees of such enormous size are unimaginable to people today because

our sense of their scale has diminished over time:

The

Man Who Loved Trees. |

|

Al Carder, author of "Giant Trees," 2005.

Photo: Daryl Stone |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Cary Fir, Lynn Valley, Vancouver, 1895.

Photo: City of Vancouver |

|

Big

Trees as Trophies The Douglas fir is a virile species known for its genetic

gigantism. It grows so tall, with a natural resistance to fire, drought, disease

and insects, that it is the world's leading big tree species. BC's tallest known

big tree was a 417 ft (127 m) "Cary Fir," named after George Cary who

was said to have cut it down in 1895 in Lynn Valley in North Vancouver (left).

Its stump diameter was 25 ft (8 m), its circumference was 77 ft (23 m), and its

bark thickness was 16 in (41 cm) at the base. The tree in the photo may also

be the Kerrisdale Tree, a giant fir cut down in 1896 by Hastings Mill for lumber.

For a discussion of these trees, see: Todd Carney:

A

Fir Tree of the Mind and John Parminter:

A

Tale of a Tree (1996). |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Habitat Encroachment Cathedral Grove is one of the few easily accessible places on the Northwest Coast where visitors can get a sense of the magnificence of the natural heritage and irreplaceable biodiversity of an ancient forest. By contrast, most of the surrounding forestlands have been ruthlessly ransacked for corporate profit with no concern for future generations. Kathryn Molloy (Sierra Club) says: "Cathedral Grove is still standing today because extraordinary citizens have been speaking up to protect it for almost a century. Everyone from loggers and corporate bosses to environmentalists has recognized Cathedral Grove as a special gem." Yet the BC government's twice thwarted plan has been to commercialize the Grove as a popular nature venue and to construct a huge parking lot. And even in 2011 the biological integrity of the famous big tree stand continues to be assaulted by the logging industry which is quietly helicopter logging in Cathedral Canyon. |

|

Cathedral Grove, ancient Douglas fir habitat.

Vancouver Island, British Columbia |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Marbled Murrelets (Brachyramphus marmoratus).

Painting by Barry Kent MacKay

Fallen totem, Nootka Trail, 3 July 2007.

Photo: Tim Gage |

|

From Sacred Symbol to Industrial Stumpage Big trees typically grow in rich valley bottoms most of which have been ravaged by industrial logging. Species which depend on old growth habitat, such as the Marbled Murrelet (left) are facing extinction along with the ancient tree veterans themselves. The unethical plundering of the last big trees in BC indicates the desperation of the wood products industry to squeeze out the last drops of lucre.

Ancient forest, Cathedral Grove.

Photo: Robert Berdan

The Aboriginal culture that depends on the old growth forests is also being degraded by the loss of the ancient trees. A totem pole fallen on the Nootka Trail in Nuu chah nulth Territory (left) testifies to enduring Indigenous values, ecological knowledge and traditional philosophy that are embedded in the rainforest. To allow this treasure to be obliterated by industrial logging is barbaric. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Boycott

BC Cedar Ancient cedar trees are in high demand in Asia for temple construction.

If BC does not stop exporting its rapidly disappearing old growth

cedar resources to supply the world's commercial demand for wood,

there will be no giant cedars and magical cedar groves left to enjoy.

Sacred groves exist in many cultures. In Japan, sacred groves are

typically associated with Shinto shrines, which are located all

over the country (right). The Cryptomeria tree is venerated in Shinto

practice and considered sacred. Many shrines originated near a big

tree (yorishiro) which has continued to be worshiped for centuries.

Also forests are associated with shrines. The Atsuta Shrine in Nagoya

is surrounded by 20 hectares of woods and the Kashima Shrine is part

of the 1,500 hectare Kashima Forest. Declared a protected area in

1953, today it is part of the Kashima Wildlife Preservation Area

which includes over 800 kinds of trees as well as a rich variety

of birds and plant life. |

|

"Sacred Grove," 1941.

Woodblock print by Toshi Yoshida |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Nisga'a mask carved from red cedar, c. 1860.

Portland Art Museum

How

Dare They Do This The destruction of BC's last surviving

intact ancient forest habitats and primeaval trees to supply

the international wood industry is shocking. Culturally modified

trees such as the ancient cedar photographed by Edward Curtis

just after the turn of the 20th century (right) are monuments

to Indigenous heritage which are being exterminated. Old growth

forest habitat along streams is vital to the spawning of wild

salmon on which First Nations are also dependent. The wrecking

of big trees and wild salmon is a hallmark of the colonial history

of Canada which continues unabated today by the industrial exploitation

of unceded native land and resources. |

|

Abuse of

Aboriginal Title & Rights While many cultures around the world protect

sacred groves, there is no acknowledgement at all by the BC government that cedar

is sacred to First Nations and inextricable to Northwest Coast

culture. It is ironic

that there is a valuable market in the collection of Northwest Coast art such

as the Nisga'a mask (right), yet no effort is made by government to protect and

preserve the cedar trees from which the art is made. This is yet another form

of the abuse of Aboriginal Title & Rights in Canada.

Culturally Modified Tree (CMT).

Edward Curtis, 1914. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Ancient Douglas fir ecosystem and awe inspiring big trees, Cathedral Grove.

Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Left and right: Archival photos show the old wagon road through Cathedral Grove c. 1910. The grand scene was described by E. Buxton in 1907:

The road for about 70 miles is almost straight and through a virgin forest of Douglas fir. The trees are from 200 to 300 ft in height, straight as a lance and most symmetrical in shape, with no branches for the first 100 or 150 ft.

The tops are like a huge plume of very dark green foliage. So graceful, so perfectly symmetrical are they that it is difficult to realize their great size.

The road winds about the shore of the lake and in and about a grove of magnificent fir trees. The trees are from 35 ft in height; all have the symmetry and beauty of the smaller firs and the grandeur of their gigantic size.

We are all silent, awed by this most impressive spectacle . . . these trees are from 600 to 700 years old, and I feel their beauty and majesty as I did that of old St. Paul's — God made them. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Chronology of Cathedral Grove The first formal call for the protection of Cathedral Grove was by botanist James Robert Anderson (1841 – 1930), son of the Scottish fur trader Alexander Caulfield Anderson (1814 – 1884), and grandson of the renowned Edinburgh botanist James Anderson (1739 – 1808). J. R. Anderson was one of the first generation Europeans to be born in the colonial territories of BC. Thus he was a first hand witness to the rapid extermination of the native Douglas fir forests by the logging industry. In 1911, as secretary of the newly formed BC Natural History Society, Anderson wrote a resolution on preserving Cathedral Grove (below) supported by the Vancouver Island Development League. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

"The supplies of wood appear inexhaustible in their natural state, but this is not the case. We have a grand heritage in our noble forests. It would be wise now before it is too late, to prevent destruction of the pristine beauty.

We intend to use every effort to induce the authorities to make such provisions. It is also to insure ourselves those who follow have at least a remnant of our grand forests.

With in easy reach by wagon road and soon by rail are the magnificent primeval forests that surround Cameron Lake. It is a representative specimen of our forests wealth which includes streams and mountains within five to 10 square miles.

From atop Mt Arrowsmith there is a panoramic view of the north and south ranges, including the Alberni Valley, Barclay Sound, the straits of Georgia and the mainland."

James Robert Anderson, 1911 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

"Brete grote boom," Cathedral Grove, 2007.

Photo: P. v. A. |

|

"Seven Wonders of Canada," 2007.

CBC webpage (Click to enlarge)

In 2007 Cathedral Grove was short listed for a national contest called "Seven Wonders of Canada" (above). Earlier, in 2005, the Canadian prime minister tributed the big tree treasures in his Canada Day speech: "Take a look at us. Behold the wonder of our landscapes; from the old growth forest of Cathedral Grove on Vancouver Island, dominated by trees hundreds of feet tall and hundreds of years old . . . "

"Beste grote boom" (best big tree) says a Dutch visitor about a tall tree in Cathedral Grove (left). The healthy 76 m (250 ft) high Douglas fir is a formidable witness to history, already 300 years old when Columbus reached America in 1492. Big trees are an icon of BC, where some of the tallest, thickest and oldest specimens in the world existed prior to post WW2 when industrial forestry and tree farms became widespread. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Weyerhaeuser old growth massacre, 24 August 2001.

Cathedral Grove, Vancouver Island, BC

Nothing has changed since environmental journalist Stephen Hume summed up his dismay over the ongoing ruination of Cathedral Grove's endangered ecosystem in 2005: "Less than 0.5 per cent of this primeval forest type, characterized by giant firs, hemlocks and cedars, survives across the Georgia Basin landscape it once dominated. In other words, more than 99.5 percent has been extirpated by loggers, developers, road builders, housing contractors, shopping malls and, of course, parking lots. . . "

Just Leave the Trees Alone. |

|

Stop Killing Big Trees Left: Paul George, founder of the Western Canada Wilderness Committee and author of "Big Trees Not Big Stumps" (2005), stands beside the huge stump of an ancient Douglas fir cut down by Weyerhaeuser in 2000. The unscrupulous American deforestation corp killed unprotected giant trees and desecrated the Cathedral Grove habitat with its logging roads and cutblocks (below).

Big tree killed by Weyerhaeuser, 2000.

Cathedral Grove, Vancouver Island |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Big trees

typically grow in the rich valley bottoms most of which have been ravaged

by industrial logging. Also Cathedral Grove contains the huge stumps of ancient

trees cut down for commercial logs (right). During the past century, the

primaeval forest homes of the big trees on Vancouver Island has been reduced

to about five percent of Vancouver. Most

of the pitifully small amount of land that has been preserved as parks comprises

high altitude locations with low biodiversity levels.

Children playing among the ancient trees.

Cathedral Grove, Vancouver Island |

|

mmmmmm

mmmmmm |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Fallen Douglas fir in Cathedral Grove, 2009.

MacMillan Provincial Park, Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

©

Credits & Contact |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|