|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Big Trees: Pictures & Politics |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

From Sacred Symbol to Industrial Stumpage |

|

Big Trees as Recreation |

|

| |

Big Trees as Natural Monuments |

|

Big Trees as Curiosities |

|

| |

Big Trees as Cathedrals of Nature |

|

Big Trees as Commercial Products |

|

| |

Big Trees as Trophies |

|

On the Wrong Side of Environmental History |

|

| |

Big Trees as Objects of Science |

|

Greenwashing Weyerhaeuser |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Big Trees as Objects of Science

Large species and giant specimens traditionally have fascinated scientists and the public alike. Monstrous dinosaurs, lumbering megatheria and, today, gigantic blue whales alike inform and fascinate. In the kingdom of plants, the colossal fossilised trunks of Sigillaria trees (right) from the Carboniferous have been outstripped in size in more recent times by the frames of big tree species such as the giant Sequoia (Sequoia gigantea). Today, these Goliaths of the plant world play an educational role and we see them as pillars of biodiversity and as keystones of ecological communities. Their disappearance under the onslaught of greedy lumber companies is as tragic and damaging to scientific inquiry and public education as is the slaughter of whales for the gratification of Japanese culinary gluttony. |

|

Sigillaria trunk, Carboniferous Age

Stanhope, East Yorkshire, UK |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Redwood cross section with dates, 2006

Myers Flat, Redwood Highway, California

The coastal redwood had the misfortune of being a top lumber species and thus it provided sawmills with a seemingly endless supply of timber for the buildup of settler society in California. By 1900, when the photo (right) was taken of a logger lying in the undercut of a giant redwood, the grand coastal forests of the Santa Cruz Mountains had already been largely destroyed. One century later – although we have a greater scientific knowledge of the value of old growth forests in absorbing carbon dioxide and mitigating climate change – ancient trees continue to be felled for wood products and are not protected by international treaties. |

|

The giant Sequoia of the Sierra Nevadas is often described as the largest organism ever to have existed on Earth, with a fossil record dating back to the age of the dinosaurs. Such big trees are commonly displayed by means of cross sectional slabs cut from their trunks, with human history dates marked on the corresponding tree rings to dramatize their exceptionally great age, such as the redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) on the left. It began its life during the Crusades in the 10th century; Magna Carta – 1113; Columbus – 1497; Pilgrims – 1600; Independence – 1768; and so on, until it was cut down for lumber in 1969.

"Big Trees of Santa Cruz"

Old postcard |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

The political cartoon "Climate Change Report" (right) by Peter Brookes illustrates the folly of continued deforestaton. Nothing has a more direct and greater impact on world climate change than cutting down forests. Not only is the forest industry responsible for almost one fifth of the world's greenhouse gas emissions, but with the continued industrial destruction of the forests we lose valuable carbon sinks. It is essential that we preserve and protect old growth forests, and the failure to do this, especially in a wealthy developed western nation such as Canada, is inexcusable.

Clearcut logging of a salmon stream, 2006

Beaufort watershed, Vancouver Island, BC |

|

"Climate Return Report"

Cartoon by Peter Brookes

The Stern Review of the Economics of Climate Change, commissioned by the UK government was released in October 2006. Action to preserve the remaining areas of natural forest is urgently needed and the report specifies that preventing deforestation would be a relatively cheap method of tackling climate change and allowing forested countries to reduce their emissions. While focus is mostly on developing nations, Canada is let off the hook. Thus clearcut logging continues even within vital community watersheds such as the Beaufort Mountains on Vancouver Island (left), not far from the world renowned Cathedral Grove. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

"Abies douglasii." Lithograph

Pinetum Britannicum, 1884

The eminent English botanist John Lindley confirmed the name Abies douglasii in his Penny Cyclopaedia entry (right). A botanical study of the cones and needles of the Abies douglasii (above), drawn by James Black and lithographed by Robert Black, was published in Edward Ravenscroft's "The Pinetum Britannicum" (Edinburgh & London, 1884). It was with this 1885 publication that the common name "Douglas fir" had its origin, largely replacing the then frequently used "Oregon pine." Unlike most common names, Douglas fir remained consistently applied to the big tree species, while its scientific name underwent frequent changes. |

|

Douglas's fir, or Douglas fir as it is known today, is the common name of a native Northwest Coast tree that is not a true fir. Following its settler "discovery," there was a long controversy about how to classify its flat and soft fir like needles and spruce like cones. 19th century botanists placed it in Pinus, Picea, Abies and Tsuga. In 1867 French horticulturist Carrière invented the new genus Pseudotsuga for it, placing it closer to the hemlock family. Its complex nomenclature includes: Pinus taxifolia (Lambert 1803); Abies taxifolia (Poiret 1805); Abies menziesii (Mirbel 1825); and Abies mucronata (Rafinesque).

"Abies douglasii." Engraving

Penny Cyclopaedia |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

"Pine Forest. Oregon." Wood engraving

C. Wilkes, US Exploring Expedition, 1845

One expedition member (who couldn't spell) noted in his diary: "Forrist trees of the largest size grow to the Very Warter's Edge where you may cut a mast or stick for a Line of Battle Ship. I never saw Sutch large forrist trees in any part of the world before." The big trees of the Columbia River were also described in "Northwest Coast" (1857) by the settler James Gilchrist Swan. Engravings of the field sketches by Swan illustrated the text (right): "The general size of the different species of fir far exceeds any thing east of the Rocky Mountains, and prime sound pine (spruce) from 100 to 280 ft in height, and from 20 to 40 ft in circumference are by no means uncommon." A fir with a circumferenceof 27 ft and a height of 230 ft (120 ft without a limb) was noted. |

|

In 1950 the Douglas fir was named Pseudotsuga menziesii, after the Scottish naturalist Archibald Menzies, who recorded the species in 1791 on Vancouver Island. One of the earliest images of a Douglas fir forest was drawn by J. Drayton and engraved by W. E. Tucker (left). It was published in Charles Wilkes, "Narrative of the US Exploring Expedition" (1838 – 1842): "the largest tree of the sketch was 39 ft 6 inches in circumference, 8 ft above the ground, and had a bark 11 inches thick. The height could not be ascertained, but it was thought to be upward of 250 ft, and the tree was perfectly straight."

"Forests in Oregon." Engraving

J. Swan: Northwest Coast, 1857 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

"The North Aerican Sylva"

Michaux and Nuttalls, 1841 – 49

The full amended title of Michaux's North American Sylva made it clear that the species of "Forest Trees" it included were "considered particularly with respect to their use in the arts, and their introduction into commerce; to which is added a description of the most useful of the European trees." The book laid the foundation of the scientific discipline of forestry in North America. Additions by Thomas Nuttall included the first scientific illustrationsin folio size of hitherto unknown native Northwest Coast big tree species. "Menzies's Spruce Fir (Abies menziesii)" (above) and "Douglas's Fir (Abies douglasii)" (right) are two examples of lithographs by Thomas S. Sinclair. For visual accuracy, the branch and cone of the species were presented in natural size.

Neither of the two scientific names given in the illustrations are today used, and Douglas fir remains the accepted common name. It honours the Scotsman, David Douglas (1798 – 1834), a botanist who explored the Northwest Coast of North America and collected the seeds of the species for the scientific collections of William Jackson Hooker at the Royal Botanic Garden. Hooker's Flora Boreali Americana (1829 – 1840) described Douglas's collections. The name Pinus douglasii (Sabine 1832) was given to a tree specimen collected by Douglas at Willamette River, Oregon, in 1830, and preserved in the Botanic Garden at Kew. |

|

The first major scientific illustrated book on American forest trees was "Histoire des arbres forestiers de l'Amerique Septentrionale" (1810 – 1813) by Francois André Michaux. The American naturalist Thomas Nuttall expanded Michaux's work with new material: "Containing all the Forest Trees Discovered in the Rocky Mountains, the Territory of Oregon, down to the Shores of the Pacific, and into the Confines of California." The six volume work was translated and published between 1841 to 1849 in six volumes with 277 coloured plates as "The North American Sylva; or, A Description of the Forest Trees of the United States, Canada, and Nova Scotia" (left).

"Abies Dougiasii." Lithograph

North American Sylva, 1841 – 1849 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

"Douglas Spruce." Wood engraving

Natural Wealth of California, 1868 |

|

The first Douglas fir specimen for botanical study was collected by Archibald Menzies on Vancouver Island in 1791. It is preserved in the Natural History Museum, London and forms the basis of the current scientific name: "Pseudotsuga. menziesii (Mirb.) Franco Douglas Fir."

Not until the mid 19th century, was the Douglas fir promoted for its commercial value, for example in the 1868 book by Titus Fey Cronise published in San Francisco: Natural Wealth of California. Its subtitle is more descriptive: "Comprising duly history, geography, topography, and scenery; climate; agriculture and commercial products; geology, zoology, and botany; mineralogy, mines, and mining processes; manufactures; steamship lines, railroads, and commerce; immigration,a detailed description of each county."

The book includes a wood engraving of the "Douglas Spruce" that emphasizes the enormous size of the big tree species by means of three tiny foreground figures (left). Both the title of the image and the additional description of the physical appearance of the Douglas fir are incorrect. The text reads: "Douglas's Fir (Abies douglasii)(Lindl.) Red Fir, or Douglass Spruce. This is . . . one of the grandest of the group of giants that form the forests of the West. This tree is generally of large size, attaining a height often of 300 ft, and a diameter of 10 ft. Wood b, but coarse and uneven in grain – the layers of each year's growth being soft on one side, and very hard on the other. The timber is much used for rough work in houses, and in ship building." |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

"Wellingtonia Gigantea," c. 1855

Lithograph, Bancroft Library |

|

Another native North American big tree species with a complex nomenclature is the giant Sequoia. Not officially "discovered" by settlers until 1852 in the Sierra Nevadas of California, the sensational new species was widely celebrated as the largest and most ancient living tree on Earth. Common names included Mammoth Tree, Big Tree, Giant Sequoia and Sierra Redwood. The first scientific description of the big tree was published in 1853 by the English botanist John Lindley who named the species "Wellingtonia gigantea" in honor of Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington. The specimen material had been taken from the chopped down "Mammoth Tree" by the English botanist William Lobb who worked for Veitch Nursery in London. The tree was pictured before her brutal demise in a lithograph (left) by "Day & Son, Lithographers To the Queen," c. 1855.

Below the image it was noted that the scene was drawn "From Nature by J. M. Lapham." Further info included the geographic location of the tree: "Standing on the Headwaters of the Stanislaus & San Antoine Rivers, in Calaveras County, California." Also the dimensions and age of the specimen were noted: "Diameter 31 ft at the base, circumference 96 ft, height 290 ft, 3000 years old." The image was likely copied in part from an 1854 lettersheet picture by J. M. Hutchings, which was widely plagiarised (below). |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Right: "Mammoth Arbor Vitae," c. 1855. Drawn "from Nature" by J. M. Lapham.

Lithograph by Briton & Rey, San Francisco. |

Left: "An Immense Tree," c. 1880. Wood engraving by Major after Kilburn. Among the many changes in this image, a dog has been added to the foreground.

|

|

|

Right: "Wellingtonia Gigantea Lindl," 1855-56.

Drawn by J. M. Lapham. Lithograph by P. W. Trap. In W. H. de Vriese, Tuinbouw-flora van Nederland (Leiden). |

Left: "Mammoth Arbor Vitae," 1861. Drawn by A. K. Kipps. Lithograph by J. M. Daniels, Boston. No credit is given J. M. Lapham for having drawn the original image.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

One of the first Europeans to see the Sequoia in life was the German explorer and nature writer Balduin Moellhausen, a protege of the famed scientist Alexander von Humboldt. Moellhausen traveled across the American West three times: with Paul Duke of Wurttemberg in 1851; with the Whipple Expedition, 1853 to 1854; and with the Ives Expedition up the Colorado River in 1858. In 1854, back home in Germany, Moellhausen was photographed in a Berlin studio as an American frontiersman in buckskin and moccasins (right).

"Wellingtonia gigantica. Lindley"

B. Moellhausen, Tagebuch, 1858 |

|

Frontiersman, Berlin, 1894

P. Barba, "Balduin Moellhausen"

Moellhausen's sketch of a giant Sequoia was the basis for a lithograph (left) that was printed as a folio illustration in his travel account "Tagebuch einer reise," published in Leipzig in 1858 (left). The book carried an introduction by Humboldt, who certainly will have been impressed by the monumental species. Indeed Thomas Jefferson, an admirer of Humboldt, was eager to convince European scientists that species native to the New World were not degenerative, as was previously thought, but rather were larger and more vigorous than those of the Old World, a famous animal example being the moose. Thus the Sequoia became emblematic of national pride and its naming a battle between nations. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

The US government's western railway explorations and surveys, in which Moellhausen participated as a member of the Whipple Expedition, are described by historians as "Humboldtian Science." The reports cost more than the expeditions themselves and were published between 1855 and 1860 in 12 massive volumes with folio illustrations and maps. Ironically, while these reports expanded scientific knowledge, they prepared the way for rampant industrial plundering and extraction of natural resources.

English botanist John Lindley noted about the big tree he had named in 1853: "Wellington stands as high above his contemporaries as the Californian tree above all the surrounding forests." Two towering Sequoias are depicted in the lithograph (right) by Scottish artist W. H. Schenk, published in "Pinetum Britannicum" (Edinburgh and London, 1863 – 1884) by Edward Ravenscroft. Not having seen the tree in nature, the artist based his image on early daguerreotypes taken at the Mammoth Tree Grove in Calaveras County. A mounted horse is included to give scale to the enormous trees yet the animal appears more like an English thoroughbred than a frontier packhorse.

In protest over the British appropriation of the Sequoia, in 1855 Albert Kellogg of the California Academy of Sciences described the species as "Taxodium giganteum." However, the disagreement over its scientific name continues today. |

|

"Sequoia Wellingtonia," 1867

Lithograph, Pinetum Britannicum |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

"Sequoia Wellingtonia, Mariposa Grove"

Pinetum Britannicum, 1884

British scientific representations of the Sequoia influenced popular imagery such as the cigarette card "Wellingtonia," published through 1922 - 1939 (right). Evidence of the success of this association is that Wellingtonia remains its popular name. While Lindley's name disappeared from scientific literature, a legitimate and widely accepted name was not found for the big tree species until the American John T. Buchholz described it as "Sequoiadendron" in 1939.

A year after the giant Sequoia had come to world attention in 1852, the haste by which ancient specimens were sacrificed for display in London was condemned: "In Europe, such a natural production would have been cherished and protected . . . what in the world could have possessed any mortal to embark in such a speculation with this mountain of wood? In its natural condition, rearing its majestic head towards heaven, and waving in all its native vigor, strength and verdure, it was a sight worth a pilgrimage to see; but now, alas! it is only a monument of the cupidity of those who have destroyed all there was of interest connected with it" Gleason's Pictorial Drawing Room Companion, 1853.

|

|

A later volume of the "Pinetum Britannicum" also included a lithograph of "Sequoia Wellingtonia" by W. H. Schenck (left). The image featured a specimen in the Mariposa Big Tree Grove with a group of sportsmen - like figures around a campfire. This semi invented scene was one of a number, featured on plates that depicted individual trees in their natural habitat. These illustrations were presented together with detailed engravings of botanical needles and fruits. Adding up to one of the great 19th century coniferous iconographies, the Sequoia plates by Schenck reinforced British hegemonic claims.

"Wellingtonia," c. 1922 – 1939

Cigarette packaging |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

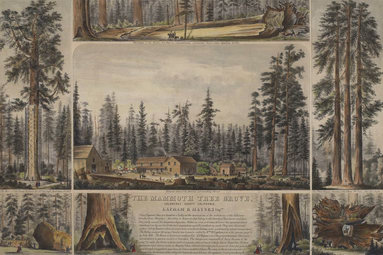

"The Mammoth Tree Grove." Calaveras County

Lithograph, 1855 |

|

The name "Washingtonia Gigantea" was cited in the descriptive text on the lithograph "The Mammoth Tree Grove" (left), printed by Britton & Rey in San Francisco in 1855. The landscapes "sketched from nature" by Thomas A. Ayres (1816 – 1858) were among the first images of the big trees. Below: "According to Botanists they belong to the Family of Taxodiaceae and have been justly named Washingtonia Gigantea. Within an area of 50 acres 92 trees of this species are found standing and are beyond doubt the most stupendous vegetable products on earth." |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

"The Mammoth Tree Grove." Lithograph, 1855. (detail)

"Sketched from Nature by T. A. Ayres." |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

"Se-Quo-Yah." Lithograph, 1836

Indian Tribes of North America |

|

The California big tree species commonly known as the coastal redwood was named "Sequoia sempervirens" in 1847 by Stephen Endlicher, a botanist and linquist in Vienna who had never been to the US. He is believed to have called the genus "Sequoia" in honour of the Cherokee Indian Sequoyah (1770? – 1843), renowned inventor of a remarkable alphabet for his native language. A portrait of "Se Quo Yah" by Charles Bird King was published as a lithograph (left) in Thomas McKenney & James Hall, "History of the Indian Tribes of North America" (Philadelphia, 1837 – 1844). The genus Sequoia may well be the only occasion whereby a North American plant species was named to tribute an indigenous person.In 1854 Joseph Decaisne, the eminent Belgian botanist and director of the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, decided that the redwood and the more recently discovered big tree, or "Mammoth Tree," of the Sierra Nevadas belonged to the same genus, Sequoia. According to the rules of botanical nomenclature, he called the new species Sequoia gigantea. Thus from the mid 19th century most botanists who wrote about the native big tree of California referred to it as "Sequoia gigantea." |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

One of the first Sequoias to be visually represented was a 325 ft specimen (right) in the Mammoth Grove of Calaveras County which was the subject of a scientific illustration in "Reports of Explorations and Survey to Ascertain the Most Practicable and Economical Route for a Railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean made under the direction of the Secretary of War, in 1853 – 54, Volumes I – XII" (Washington 1855 – 1861). The three part Volume V (1856) described the geology, deserts, valleys and flora of southern California. It included maps, geological cross sections, lithographed landscape views and engravings. The Sequoia was depicted in "Part 2. Routes in California to Connect with the Routes near the Thirty Fifth and Thirty Second Parallels, Explored by Lieutenant R. S. Williamson, Corps of Topographical Engineers, in 1853. Geological Report, by William P. Blake, Geologist and Mineralogist of the Expedition," as Plate XIII, "Mammoth Tree, Beauty of the Forest." See: Reports of Explorations & Surveys (University of Michigan). Following the publication of this work, Blake became a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences.

The 1856 lithograph "Beauty of the Forest" (right) was based on field sketches by Blake, who was credited below the image as the draftsman. The lithography firm owned by Thomas Sinclair in Philadephia was credited with publishing the image. Sinclair was a Scottish artist who had trained in Europe before establishing himself as a lithographer in Philadelphia in 1838. He had never been to California nor seen a Sequoia. Although not botanically accurate, the image communicates the scale of the tree in relation to the figure at its base and illustrates the text which states, "the grandeur of the scene cannot be described." |

|

"Mammoth Tree, Beauty of the Forest"

Lithograph, 1856 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

"The Mammoth Trees of California"

Engraving by G. K. Stillman, c. 1855

The engraving "The Mammoth Trees of California" (above) by G. K. Stillman was published c. 1855 as a broadsheet. Its subtitle, "Sequoia gigantea," indicates the widespread acceptance of the scientific name. Engravings of individual Sequoias, such as "Satan's Spear" (right), appeared in one of the earliest guides to the big trees, "Scenes of Wonder and Curiosity in California" (1862) by James M. Hutchings. The artist who sketched the 78 ft in diameter tree explained: "We came to a large stem, whose top had been stripped of its branches, giving it somewhat the resemblance of an immense spear, and forcibly reminding one of Milton's description of Satan's weapon of that name." John Muir was later fascinated by the Sequoia's immunity to all dangers over thousands of years except for lightning. |

|

"Satan's Spear." Engraving

Scenes of Wonder, 1862 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

One of the earliest scientific descriptions of the

Yosemite Valley and the "Big Trees of California" was Josiah D. Whitney's the

Yosemite Book

(New York, 1868). Whitney was a professor of zoology and physiology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His book featured 28 photographic plates by Carleton E. Watkins, such as the "Giant Grizzly" in the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees (right). For scale, Galen Clark, guardian of the grove, appears at the base of the tree. Watkin's photos had played an important role in convincing the US Congress and President Lincoln to protect the Mariposa Grove as a public park in 1864.

Whitney described the big trees as "truly remarkable productions of the vegetable kingdom" and he complained about how little had been published about them: "No correct statement of their distribution or dimensions has appeared in print; and, if their age has been correctly stated in one or two scientific journals, no such information ever finds its way into the popular descriptions of this tree, which are repeated over and over again in contributions to newspapers, and in books of travel. For all the statements here made, the Geological Survey is responsible, except when it is otherwise expressly stated." Whitney provided a history of the botanical name of the Sequoia, which he described as a "complicated subject." For a more recent nomenclature, see

A Botanist's View of the Big Tree (Robert Ornduff, 1994). |

|

"Base of the Grizzly Giant"

The Yosemite Book, 1869 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Galin Clark's cabin, Mariposa Grove

Old postcard

Galen Clark came to California in 1848 in search of gold. Credited with "discovering" the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees, he acted as its guardian for over half a century and became a legend who was often pictured on tourist postcards such as the one above that included a view of his picturesque cabin. In the postcard on the right he is seen standing beside the infamous Grizzly Giant. According to text on the card, the Giant's estimated age is "6,000 years, the oldest living thing on Earth" with a diameter of 33 ft, circumference 134 ft and bark 2.5 ft thick. In the introduction to his book, Galen Clark described the world renowned species as Sequoia Washingtoniana: Big Trees of California (1907). |

|

"Galen Clark, Discoverer of the Grove"

Old postcard |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Samuel Kneeland, a Boston physician and professor of zoology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, took part in a couple of collecting expeditions to California between 1869 and 1871. His illustrated account of the big trees was published: Wonders of the Yosemite Valley (1872). One of the wood engravings was "Cone and Foliage" (right), printed in "Full Size" as the "grandest type of the vegetable world." Kneeland explained that the genus was "known in science as Sequoia gigantea." This same unacknowledged engraving had been published ten years earlier in J. M. Hutchings' Scenes of Wonder, and it illustrates the widespread practice of plagiarism, also by scientists.

Forest with two Sequoias on left. Engraving

J. Muir, The Mountains of California, 1894 |

|

"Cone and Foliage of the Mammoth Tree"

Engraving, S. Kneeland, 1872

Conservationist John Muir championed the Sequoias early on, marveling at their immortal - like longevity and dispairing over their loss as a result of lumbering: "Any fool can destroy trees," he wrote "They cannot defend themselves or run away. And few destroyers of trees ever plant any; nor can planting avail much toward restoring our grand aboriginal giants. It took more than three thousand years to make some of the oldest of the Sequoias, trees that are still standing in perfect strength and beauty, waving and singing in the mighty forests of the Sierra. Through all the eventful centuries since Christ's time, and long before that, God has cared for these trees, saved them from drought, disease, avalanches, and a thousand storms; but he cannot save them from sawmills and fools"

Our National Parks (1901).

An uncredited wood engraving (left) picturing two Sequoias, illustrated a chapter on forests in Muir's influential book, in which he described the Sequoia gigantea, the Big Tree, as the "kingof all the conifers in the world" and "the noblest of a noble race"

Mountains of California (1894). |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

"A Log of Bucks." Stereoview, c. 1875

Eadweard Muybridge (click to enlarge)

While the "Sequoia" genus embodied an indigenous identity, the native peoples of the Sierra Nevadas were brutally forced from their land beginning in the mid 19th century with the European "discovery" of Yosemite Valley. Photographer Eadweard Muybridge was hired by the California Geological Survey to document the Sierras and he also produced a series of stereoviews of Yosemite Valley. His deprecating image of the Paiute people c. 1875 (above) contrasts with the description of the tribe by ethnologist Stephen Powers: "The California big tree is also in a manner sacred to them, and they call it woh woh' nau, a word formed in imitation of the hoot of the owl, which is the guardian spirit and deity of this great monarch of the forest. It is productive of bad luck to fell this tree. . ." Tribes of California (1877). |

|

General Sherman, Sequoia National Park

Photo: Flickr |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Sequoia National Park was established in 1890, in part to prevent the commercial ruination of the world's largest known Sequoia, a specimen named General Sherman after the Civil War hero (above, right). But until the National Park Service was established in 1916, the park had to be guarded by a US cavalry troop under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior, to prevent the logging and mining companies from plundering the surviving Sequoias.

John Muir warned that while "our forest king" might live forever in Nature, "It is rapidly vanishing before the fire and steel of man; and unless protective measures be speedily invented and applied, in a few decades, at the farthest, all that will be left of Sequoia gigantea will be a few hacked and scarred monuments"

Mountains of California (1894).

Sequoia National Park, 2007

Photo: Flickr |

|

Sequoia National Park

Photo: Flickr

John Muir had nothing but contempt for the logging industry, "robbing the country of its glory and impoverishing it without right benefit to anybody, a bad, black business from beginning to end." A world renowned natural wonder, yet neither fame or science could save the giant Sequoia from commercial greed. Indeed under the guise of "scientific forestry" the destruction of the Sequoia forest habitat continues today by Sierra Pacific Industries. Even the Giant Sequoia National Monument, founded in 2000, has been ineffective protection against the mighty lumber industry. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

"They are not like trees, they are like spirits. The glens in which they grow are not like places, they are like haunts — haunts of the centaurs or of the gods. The trees rise up with dignity, power, and majesty, as though they had been there forever.

They were more like gods than anything I have ever seen. They seemed to be thinking. One felt that presently they would march to wipe out everything mean or base or petty here on Earth. The stars shone about their heads like chaplets."

John Masefield

English poet laureate, 192

Right: Congress Group, Sequoia National Park, California |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

"Redwood peeling," California, c. 1900

Photo: North Carolina State University |

|

Too little emphasis is put on the extent to which forestry science has become instrumentalized by the forest industry. This process is most vividly exposed by the fate of the coastal redwood forests, which within a century of industrial logging had been reduced by 97 percent. The German born and educated forester Carl A. Schenck (1868 – 1955) is regarded as a founding figure of scientific forestry in the US. His 1954 manuscript "The Dawn of Private Forestry in America, Recollections of a Forester Covering the Years 1895 to 1914" includes an image of an "over mature" redwood forest (left) being "harvested." Today we see this as a portrait of the destruction of a vital ancient trees habitat. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

"Undercut in redwood," c. 1900

Photo: North Carolina State University

Schenck's manuscript was republished in 1974 by the American Forest History Society under the title "The Birth of Forestry in America: Biltmore Forest School, 1898 – 1913." Again in 1998 it was republished by the Forest History Society in cooperation with the Cradle of Forestry in America Interpretive Association and the US Forest Service History Program under the self promoting title "Cradle of Forestry in America: The Biltmore Forest School, 1898 – 1913." Many photos in the Schenck manuscript depict the destruction of Northwest Coast big tree species, such as "Felling a large fir" (right). Such native ancient trees were tributed for the amount of board footage they contained rather than beauty and awe. Commercial comparisons were often given on trophy photos to promote the logging industry. |

|

Schenck was the founder, in 1898, of the Biltmore Forest School on the estate of George Vanderbilt in Asheville, North Carolina. A revised edition of the Schenck manuscript was published in 1955 by the industry - patronized American Forest History Foundation at the Minnesota Historical Society under the title "The Biltmore Story: Recollections of the Beginning of Forestry in the United States." Schenck's manuscript included a photo of a mortally wounded big tree in California (left) with the title "Undercut in redwood 25 ft in diameter."

"Felling a large fir," c. 1900

Photo: North Carolina State University |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

"History Log," Humboldt Redwoods State Park

Photo: Flickr |

|

Dendrochronology, or tree ring dating is a scientific method of dating based on the analysis of tree ring growth patterns. Trees develop annual rings of different properties depending on the weather in different years, providing a unique and valuable match of both time and location. Yet dendrochronology has been vulgarized by the forest industry in the guise of science and public education. Cross sections of healthy ancient trees are typically donated by logging companies to be displayed in parks. Certain tree rings on the slab are identified (left); for example the innermost tag marks the 1215 signing of the Magna Carta, an event that occurred when the tree was a sapling. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Gallery – Cross Sections for Dendrochronology |

|

|

|

|

Redwood cross section with dates

Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park |

Redwood cross section with dates

Dyerville, California |

Tree sprouted in 1293. Was felled

for paper in 1963, Puget Sound, Wa

|

|

|

|

|

Redwood cross section, 1949

Fort Bragg, California |

Redwood cross section

Big Basin Redwoods State Park |

"Giant Sequoia Tree, 2000 years old"

Museum of Science, Boston |

|

|

|

|

"1000 years old"

Redwood Highway |

Redwood cross section with dates

Myers Flat, Humboldt County |

Redwood cross section with dates

Muir Woods, Marin County |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Dendrochronological cross sections (above) are abundant on the Northwest Coast, especially in logging communities where these relics are all that remains of the once magnificent primaeval temperate rainforest. One of the largest cross sections of a giant Sequoia has remained on view in the grand hall of the Natural History Museum in London for over a century (right). The exceptionally large and perfectly formed Sequoia, named Mark Twain, was cut down in 1891 by the Kings River Lumber Company. Its stump remains in the "Big Stump Grove" at Sequoia National Park.

The first chief of the US Forest Service, Gifford Pinchot, expressed his admiration for the Sequoia in his essay "A short account of the big trees of California,"published in 1900 by the US Dept. of Agriculture Division of Forestry Bulletin. Pinchot exclaimed that Sequoia is "the grandest, the largest, the oldest, [and] the most majestically graceful of trees . . ." At the same time, he stuck to his conviction that "the majority of the Big Trees . . . certainly the best of them, are owned by people who have every right, and in many cases every intention, to cut them into lumber."

"William Astor's Dining Table," c. 1895

Photo: Humboldt State University Library |

|

Sequoia cross section, 2008

Natural History Museum, London

Slabs from the Sequoia's coastal redwood cousin, Sequoia sempervirens, were also sent to London for display. The magazine Scientific American (27 November 1897) included an essay entitled "The Giant Redwood Trees of California." Its subject was a redwood that had been cut down by the Vance Lumber Company in Humboldt County so that a cross section from it could be sent to William Waldorf Astor in London to fulfill his wager "To seat 40 guests at a table made of a slice of a Big Tree." A photo of the mutilated tree was published with the caption "William Astor's Dining Table on Its Way to the Coast" (left). The glass plate negative had been taken by A. W. Ericson, a photographer based in Arcata, Humboldt County. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Another undated photo by Ericson depicts a redwood cross section in the lumberyard owned by John Vance (right). It is believed to be the same section, 14 ft, 5 inches in diameter, that was sent to Ascot in London in 1897. In this scene, two men with axes pose in front of the section, as big game hunters with their trophy. Vance was one of the first settlers in Eureka, Humboldt County, where he founded a sawmill in 1853. When it burned down in 1893 he started a new operation at Samoa on Humboldt Bay. Vance sold the Samoa sawmill to the Hammond Lumber Company in 1900 which operated until1956 when it was bought by the Georgia Pacific Company. In 1972 the Samoa industry was sold to the Louisiana Pacific Company which finally abandoned it in 1980 when the last lucrative old growth timber had been cut down. Thus Pinchot's principle that scientific forestry stands for both conservation and development is an oxymoron. |

|

"Among the Humboldt Redwoods"

Photo: Humboldt State University Library |

|

| |

|

|

| |

©

Credits & Contact |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|