| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Cathedral Grove, British Columbia |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Our Big Tree Heritage |

|

Ancient Forest Extermination |

|

| |

Linking Two Biospheres |

|

Protecting Park Values |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

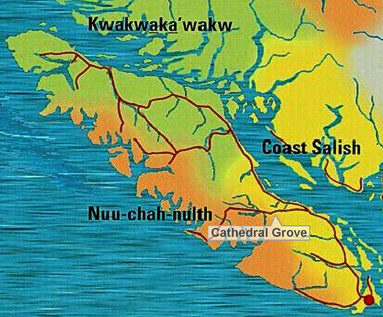

Linking Two Biospheres

Cathedral Grove is located on Vancouver

Island (right) and is part of the province of British Columbia

(BC), Canada. About the size of Denmark, Vancouver Island is

the largest island on the Pacific Coast of North America. Only

a few hours drive from the capital city of Victoria, Cathedral

Grove is the gateway to the West Coast wilderness where Pacific

Rim National Park is a popular destination. The Cathedral Grove

Watershed is a vital wildlife corridor in the Beaufort Range

and links two UNESCO designated Biosphere Reserves: Clayoquot

Sound to the West and Mount Arrowsmith to the East. Before

the advent of large scale industrial logging some 50 years

ago, Cathedral Grove was at the heart of one of the most magnificent

rainforests on Earth; today it is surrounded by cutblocks

and tree plantations, the result of years of unrelenting commercial

exploitation. |

|

Cathedral Grove Wildlife Corridor.

Vancouver Island, British Columbia |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Painting of Mount Arrowsmith, c. 1895.

Vancouver Island, British Columbia |

|

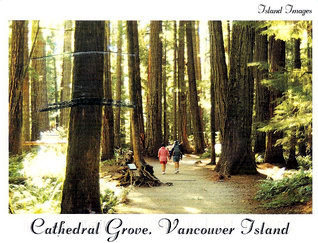

Cathedral Grove, Vancouver Island.

Postcard |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Cathedral Grove: Linking Clayoquot Sound and Mount Arrowsmith Biospheres.

Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

"Nowhere in the world are the temperate rainforests more

exuberant than in our Pacific Northwest. Enormous conifers, some over four metres in diameter,

rise out of the carpet of moss to reach 100 metres into the sky.

We stand in awe, knowing that many of these heritage trees are over 1000

years old and knowing that this magnificent forest is the result of natural

processes since the glaciers retreated about 14,000 years ago. Nowhere

can we better feel the flow of life and our place in the universe. . .

In less than 20 years any heritage tree that is not protected will most

likely be logged. And we shall never be able to get any of them back."

Bristol Foster, 1986

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

The

Parking Lot Cathedral Grove is bisected by the Alberni Highway (right),

the sole transportation route between the East Coast of Vancouver Island

(Nanaimo, Qualicum Beach and Parksville) and the more remote, less populated

western side where the four largest communities are Port Alberni, Bamfield,

Ucluelet and Tofino. Colonists set up the first export sawmill in BC at the

head of Alberni Canal in 1861 and in the 1890s a nearby port was developed

by settlers. In 1912 both sites incorporated and the town that developed

was based on the logging industry. Bamfield, Ucluelet and Tofino are small

fishing communities now dependent on nature tourism. |

|

Alberni Highway, Vancouver Island

British Columbia

(Click to enlarge) |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Clayoquot Sound, West Coast, Vancouver Island.

Photo: Adrian Dorst

First Nations, local communities, and the federal and provincial governments founded Clayoquot Sound Biosphere & Mount Arrowsmith Biosphere in 2000 as UNESCO reserves. While this designation acknowledges Aboriginal Title and Rights, it has been ineffective in protecting indigenous natural resources. The Arrowsmith massif (right) was named c. 1853 after the English cartographers Aaron and John Arrowsmith. Its ancient Nuu–chah–Nulth name is "Kuth Kah Chulth," meaning "that which has sharp pointed faces." |

|

Barkley and Clayoquot Sounds are the ancient homelands of the Nuu–chah–Nulth aboriginal peoples, known as the Nootka Indians until 1980. Only a small area of the still intact temperate rainforest (left) is protected from industrial logging. Established in 1970, Pacific Rim National Park Reserve covers 511 sq km of land and ocean in three separate regions (Long Beach, Broken Group Islands, West Coast Trail) and has become a popular tourism destination.

Mount Arrowsmith.

Vancouver Island, British Columbia |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

View from Mount Arrowsmith.

Photo: Eric Praetzel

Arrowsmith is the highest mountain in the Beauforts, a mountain range called "Yuts–whol–aht" in the Nuu–chah–Nulth language. It means "walking through the face of the mountains" and describes the ancient trading trail that linked the West and East Coasts of Vancouver Island. Both the aboriginal trail and Cathedral Grove connect two coastal UN Biosphere Reserves while serving as a "Wildlife Corridor" for species such as bears (right). |

|

Arrowsmith massif was named by Captain G. H. Richards of the Royal Navy, who surveyed much of coastal Vancouver Island and the adjacent mainland in the 1850s prior to colonization in 1858. In the early 1900s the Island was surveyed to set up commercial timber blocks. These were exploited most voraciously following the advent of industrial logging in the 1940s. Today a view from Mt Arrowsmith above Cathedral Grove shows the forest to be a checkerboard of clearcuts (left).

Black bear in stream, Beaufort Range.

Photo: Klaus Rademaker |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

During the late 1960s, MacMillan Bloedel began to cut logging roads into the intact wilderness forest on lower slopes of Mt Arrowsmith and Mt Cokely, part of the Cathedral Grove Watershed. Protests by hiking and ski enthusiasts pressured the logging company to release 607 hectares of logged off land on the north slope of Mt Cokely to the Alberni Clayoquot Regional District for a public ski area called Mt Arrowsmith Regional Park. The small park includes neither the Arrowsmith massif (right) nor the summit of Mt Cokely.

Tom Qualicum (right) and his family, c. 1900.

Photo: British Columbia Archives |

|

Mount Arrowsmith massif and cairns.

Vancouver Island, British Columbia

The earliest ascents of Arrowsmith were likely by First Nations Peoples. Left is a c. 1900 family of Coast Salish - Qualicum Chief Tom Qualicum (far right). In 1887 he and his son led the first Europeans, John Macoun (naturalist to the Canadian Geological Survey) and his son, to the summit of what was then believed to be the highest mountain on Vancouver Island. Another early ascent by Europeans in 1901 was guided by Nuu–chah–Nulth Tseshaht Charlie Clutesi and included two prominent scientists and nature lovers: from Ottawa the government entomologist James Fletcher and from Victoria the Deputy Minister of Agriculture James Anderson. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Culturally modified trees, Cathedral Grove.

Photo: Richard Boyce

A massive fire occurred in the Cathedral Grove Watershed in 1885 and the peeled CMT cedars (above) have grown up under the protective canopy of the ancient fir forest which survived the fire. Much is to be learned from indigenous foresters who before contact managed the ancient "working forests" sustainably over many centuries. Since colonization in 1858 and the advent of industrial forestry, the giant trees have been the object of commercial extermination, including the natively called "Tree of Life," the red cedar (right).

Two ancient cedars, Clayoquot Sound

Photo: Friends of Clayoquot |

|

Both naturalists were amazed by the size of the ancient trees in Cathedral Grove and both pleaded with the Canadian Forestry Association to save them from the axe; Fletcher in 1901 and Anderson in 1919. The latter made the case that the big trees were a "natural monument erected by the hand of God." Today we recognize the presence of indigenous culture in Cathedral Grove, shown by hundreds of "heritage trees" These bark peeled culturally modified trees (CMTs) include some cedars with "strip catfaces" more than 100 ft long. There are also a number of larger cedars with dark cavities still standing that show evidence of the burn felling process (left).

"Putting an undercut in red cedar," c. 1920.

Photo: British Columbia Archives

During the 1980s the Tla o qui aht indigenous people of Clayoquot Sound fought to save the ancient cedars and establish a Nuu–chah–Nulth Tribal Park on Meare Island. But the risk of full and final extermination continues as the big cedars become increasingly rare (left). |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Indigenous languages and cultural groups.

Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada

On the Coast Salish side, the Qualicum First Nation is closest to Cathedral Grove; on the Nuu–chah–Nulth side it is the Hupacasath First Nation. Welcoming visitors to Port Alberni are two carved figures with outstretched arms standing on the Somass River waterfront (right). The female and male figures were carved by Hupacasath artists Rod Sayers and Cecil Dawson from two ancient cedar trees, one 400 years old; the other 600 years old. Raised in 2005, the figures are part of a Hupacasath project to increase tourism revenue; also on view is a life scale carving of a Nuu–chah–Nulth whaling canoe. A carving shed and a Transformation Interpretive Centre are planned. The project is changing the industrial identity of Port Alberni and educating tourists about the rich indigenous heritage of the region. |

|

A map of Vancouver Island shows the territories of three indigenous peoples, each with distinct social and cultural characteristics (left): Kwakwaka'wakw (green); Coast Salish (yellow); and Nuu–chah–Nulth (orange). Cathedral Grove is on the sheltered lee side of the Beaufort Range that divides the Island from north to south, acting as a natural boundary between traditional territories.

Welcome figures, Port Alberni.

Photo: Karen Wonders |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Hupacasath Chief Judith Sayers (right), 2003.

Photo: British Columbia Lieutenant Governor |

|

In 2003 Judith Sayers (Ke Kin Is Uqs) welcomed the Governor General of BC to the magnifcent new cedar Hupacasath House of Gathering (left). Sayers served as Hupacasath chief councillor from 1995 to 2009 and she remains the tribe's chief treaty negotiator. Trained as a lawyer, Sayers launched successful legal actions in 2005 and 2008 against the BC Ministry of Forests and the logging corporations (Weyerhaeuser – Brascan – Island Timberlands). This was in response to Weyerhaeuser's removal in 2004 of 70,300 hectares from Tree Farm Licence 44, much of which is contested Hupacasath Territory.

In two groundbreaking decisions, the court ruled that the Crown (BC government) had a duty to consult with and accommodate the Hupacasath over issues such as access to sacred sites, harvesting of cedar and traditional medicines and hunting. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Chiefs Kim Recalma Clutesi and Adam Dick.

Photo: Richard Boyce |

|

The Cathedral Grove Watershed is in Tree Farm Licence 44. Both Hupacasath Chief Council Judith Sayers and Qualicum elected Chief Kim Recalma Clutesi (Ogwi Lo Gwa) have taken an interest in the protection of Cathedral Grove. University educated Chief Reclama Clutesi was raised on the Qualicum Indian Reserve and is the daughter and potlatch recorder of Hereditary Chief Ewanuxdzi. She is seen (left) with her husband, Tsawataineuk Hereditary Chief Adam Dick (Kwaaksistala). He was raised in Gway'i (Kingcome Inlet) where he was traditionally taught by his grandparents. Chief Adam Dick is a fluent native speaker and an expert on Kwakwaka'wakw culture. The couple is in great demand for their wide range of skills which include ethnobotany, traditional food gathering and preparation, repatriation of ancestral remains and potlatch ceremonials. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Painting by Tseshaht George Clutsei.

Maltwood Museum and Gallery

Located on Tseshaht land, the Alberni Indian Residential School was the vile instrument of state repression by which native children were "acculturated." Tsesaht George Clutesi (1905 – 1988) was one of many who suffered greatly here. Later he became a notable writer and artist (above), tributed by Emily Carr and much respected for his teaching of Tseshaht values, beliefs and traditions.

The original site of what is now called Port Alberni was inhabited by the Tseshaht (Nuu–chah–Nulth) when colonizers seized it by force: first the Spanish, then the British when armed vessels under Gilbert M. Sproat sailed up the Alberni Canal in 1860. Sproat describes the refusal of the Tseshaht Chief to give up his tribal land and the Tseshaht resistance to the invaders in the opening to his book:

Scenes and Studies of Savage Life (1868). The British branded the Tsesaht as "savages" who did not legally own their land because they did not use it for cultivation.

House of Tseshaht from the road, 2008 |

House of Tseshaht from Somass River, 2008 |

|

|

Totem pole, Tseshaht Gas Station, 2006.

Port Alberni, Vancouver Island

Two magnificent totem poles (above) stand at the

Tempo Gas Station on the Tseshaht Indian Reserve in Port Alberni.

The Pacific Rim Highway in the direction of Tofino passes through the

Reserve. Raised on 29 June 2006, the two 25 and 27 ft high totem poles

were commissioned by the Tseshaht band council. They were carved under

the direction of the well known international Hesquiaht carver Tim Paul,

by Willard Gallic Jr., Tobias Watts and Gordon Dick. Old growth red cedar

is not only vital to the art of totem poles but also to other forms of

indigenous culture including archictecture.

On 13 October 2008 the masterpiece "House

of Tseshaht," a

multiplex building on the Somass River in Port Alberni opened

(left). This award winning model of green architecture was constructed

with massive old growth timber harvested from nearby Tseshaht lands. Its

historically important location on the Somass River is a source of strength

and inspiration for the Tseshat First Nation.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

For over 30 years the Tseshart administration centre was located in the Alberni Indian Residential School, ever since the building was abandoned in 1973 and "given" to the Tseshaht. The despised symbol of oppression was finally torn down in February 2009. Colonial history celebrates European heritage and little indigenous heritage in BC has been preserved. Before contact and colonization, the West Coast was one of the largest populated non – agricultural regions in the world. Yet it possessed far more dietary abundance and variety than European societies.

Adam Horne, one of the first settlers on Vancouver Island, is seen in a fringed frontiersman jacket in a studio portrait with his wife c. 1855 (right). Born in Edinburgh, Horne was a Scottish fur trader employed by the Hudson's Bay Company. He was credited with "discovering" an ancient indigenous trading trail across Vancouver Island that became the first settler route to Alberni Valley. Mt Horne and Horne Lake, the headwaters of Qualicum River, are named after him.

Cleared land near Horne Lake, c. 1910.

Photo: British Columbia Archives |

|

Adam Grant Horne and wife, c. 1855.

Photo: British Columbia Archives

The first task of settlers was to clear the land of its primaeval forests, to convert it from useless wilderness to valuable grazing or agricultural land. Deforestation was encouraged by the colonial government which enacted a Land Ordinance in 1860 that assigned leases of "unoccupied Crown lands" to individuals and corporations engaged in "cutting spars, timber or lumber." An 1866 Pre Emption Ordinance (in place until 1953) barred First Nations from pre empting land despite the fact that almost all Crown land was contested by Aboriginal Title and Rights. The primaeval forests around Horne Lake, just north of Cathedral Grove, were for the most part gone by 1910, only a few scattered big trees remained (left). |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Dunsmuir Land Grab, E&N Railroad Land Grant, 1883.

British Columbia Encyclopedia (text added) |

|

First Nations have never shared in the enormous

profits made from the industrial logging of their territories.

Cathedral Grove is located in the large area of Vancouver Island

that was part of a murky "land grant" deal in 1883, benefitting

the Scottish railway baron Robert Dunsmuir who was also a member

of the provincial legislature, and his crooked

American partners. This "Dunsmuir

Syndicate" were able to grab a fifth of Vancouver Island for

themselves (left). Note the straight surveyed line of its western

border that bisects Port Alberni. Dunsmuir robbed the government

of two million acres of forest land in exchange for the construction

of just 77 miles of track of the so called "E&N

Railroad," the

western end of the transcontinental railway across Canada. In 1905

Robert's son James Dunsmuir, sold the E&N to Canadian Pacific Railway,

which in turn sold huge sections of land to logging companies. The

most profitable heavy timber lands were identified and surveyed into

timber blocks for future exploitation. One of the timber amalgamations

was called the "Cameron

Division" after Cameron Lake which had been named in 1860 to honour

a Scottish fur trader and settler, the first judge of the new colony

of Vancouver Island. Both Cathedral Grove and Mt Arrowsmith lie within

the Cameron Division and have suffered the ravages of being "privately

owned" forest land ever since.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Railway engineers, Cameron Lake, 1910.

Photo: British Columbia Archives

The first organization to lobby for the protection of Mt Arrowsmith was the Vancouver Island Section of the Alpine Club of Canada and many members stayed at the Cameron Lake Chalet. One of the first groups of tourists to arrive at Cameron Lake in 1912 was called "R. M. Custance's Comedy Company" (right). At about the same time, a pack trail was completed from Cameron Lake to an overnight hut at 4200 feet on the slopes of Mt Cokely. From here visitors could continue on a more challenging hike to the summit of Mt Arrowsmith. The trail, known as the Old Arrowsmith Trail, and also the Cameron Lake Trail, is the oldest intact trail on Vancouver Island and continues to be used extensively. |

|

When the E&N Railroad from Parksville reached the eastern end of Cameron Lake in 1909, the Cameron Lake Chalet was built as a resort destination to promote recreational tourism. It remained popular for five decades. The big trees attractions of Cathedral Grove acted as a detriment to the logging in the area even though it had been surveyed into cutblocks. In 1910, to make way for the railway tracks to Port Alberni, engineers moved the old wagon road from the north side of Cameron Lake to the south side, through Cathedral Grove.

Cameron Lake Railway Station, 1911.

Photo: British Columbia Archives |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Mount Arrowsmith Park

Hiking Trails (Click to enlarge) |

Historic Old Arrowsmith Trail

from Cameron Lake |

|

|

The Old Arrowsmith Trail begins at Cameron Lake, to the east of Cathedral Grove (left). Despite sharing its name with the Mount Arrowsmith Biosphere, the Arrowsmith massif is not protected. It is part of "Block 1380," a 1300 hectare section of Crown land which includes the ridges and peaks of Arrowsmith and Cokely as well four sub-alpine lakes. Block 1380 is located next to the small Mt Arrowsmith Regional Park, which lies on the lower slopes of Mt Cokely and encompasses a former ski hill. The Cameron Division Tree Farm Licences that surround Mt Arrowsmith and Cathedral Grove on all sides are owned by the logging company Island Timberlands (formerly Brascan – Weyerhaeuser – MacMillan Bloedel). The area is extensively used for hiking, climbing, nature study, wilderness camping, backcountry skiing and snowshoeing. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

A map of hiking trails in the proposed Mount Arrowsmith Park was issued by the Alpine Club of Canada and the Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC (above). Protection for Block 1380 was first attempted in 1989 by the Public Access Resolution Committee, a grassroots organization that formed to protect against the ski hill developers. In 2001 a deal between the Regional District of Nanaimo (where Mt Arrowsmith is located) and the timber companies resulted in the leasing of the land through which the Old Arrowsmith Trail runs, from Cameron Lake (right). To celebrate its 100th anniversary in 2006, the Alpine Club wished (to no avail) that a Mt Arrowsmith wilderness park would be created.

Cutblocks and MacMillan Park, 1953 (Click to enlarge).

Government of British Columbia Library |

|

Cathedral Grove and Cameron Lake.

Vancouver Island, British Columbia

Mount Arrowsmith Biosphere contains two watersheds that supply community drinking water: on the north side is the Englishman River; and on the south side are the Little Qualicum River and Cameron River. By the late 1960s the forest destruction companies began blasting logging roads into the lower slopes of Mt Arrowsmith. This and later encroachments have been the source of environmental protests ever since.

A 1953 map of "MacMillan Provincial Park" (left) shows how the tiny park at the base of Mt Arrowsmith is surrounded by cutblocks, each indicated by "BK" and a number. Even the historic Old Mt Arrowsmith Trail from Cameron Lake is leased from the logging companies Timberwest and Island Timberlands (formerly Weyerhaeuser - MacMillan Bloedel). Most of the Cameron Division cutblocks were long ago clearcut logged. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Vancouver Island: deforestation over 50 years.

Sierra Club British Columbia (Click to enlarge) |

|

Some of the tallest, largest and oldest conifers in the world grow on Vancouver Island. The Sierra Club maps (left) show the shocking rate at which the ancient rainforest has been exterminated within a fifty year period between 1954 and 1999. During the past two decades, old growth deforestation has continued apace. The yellow, or most heavily deforested, areas correspond with the Dunsmuir Land Grab of 1883 that subsequently came under the ownership of a few multinational logging corporations. The temperate rainforest has a greater biomass than any other same-sized ecosystem on Earth. Less than 9% of the ancient forest remains on Vancouver Island. To date clearcut logging has destroyed 85 of the original 91 watersheds on Vancouver Island, leaving only six precariously remaining. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Private forest lands, Vancouver Island, 2007.

Government of British Columbia (Click to enlarge)

It is alarming that an American lobby group promoting private managed forestland is gaining power in BC, its map of Vancouver Island (above) shows almost the entire land base as a commercial forest. By now, it is well known that commercial forestry is characterized by fake science, rapid liquidation, tree farm conversion and nature degradation. Increasingly private forest land is converted to profitable real estate development and urban sprawl.

Tree monocultures which are engineered to produce economic timber lack the biological complexity of intact forest ecosystems. A tiny Douglas fir seedling growing in front of a huge old charred cedar stump (right) from a tree probably six or seven centures old, was photographed in 1974 on a tree plantation near Port Alberni for the US Environmental Protection Agency as an example of scientific forestry. The conversion of forestland that began in the 1940s resulted in massive erosion and decimation. Ancient forests cannot be replaced: they are the foundation of First Nations cultures and provide healthy watersheds, salmon spawning streams and wildlife habitat. Ancient forests also sequester carbon, provide drinking water and generate tourism. |

|

Contested indigenous land in BC and Crown (publicly owned) land continues to be converted to private land through schemes engineered by big business and its government accomplices. The first such conversion of questionable legality, the "Dunsmuir Land Grab" involved almost a quarter of Vancouver Island. This area is seen in green on the map (left) and yellow in the above Sierra Club map. In the 1950s, most Crown forestland was converted to "Tree Farm Licences" (pink areas) which today are increasingly being redefined as "Private Land" (dark pink). In 2009, as part of this conversion process, the government announced its new scheme of "Commercial Forests."

Huge stump and seedling, 1974.

US Environmental Protection Agency |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Right: Ruth Masters, centre, at the Comox Glacier,

1938. |

Left: Ruth Masters

at Cathedral Grove, protest in 2001: "Senior Tree Hugger."

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Roosevelt elk in Cathedral Grove, 2005.

Photo: Richard Boyce

In 2007, at 86 years old, Ruth Masters challenged TimberWest's

plan to log the trail to Comox Glacier and received national press. The official

response, from spokesperson Steve Lorimer was that the company had no interest

in cutting back its profit by leaving buffers to the hiking trails – as

requested by the Federation of Mountain Clubs and the Comox District Mountaineering

Club. Logging roads in buffer zones to parks cause much ecological damage and

fragment wildlife populations. Cathedral Grove, a rare old growth forest habitat,

is critical to the elk (right) yet it too is being assaulted by Island Timberlands. |

|

Strathcona Park, the "triangle of mountainous virgin land," located just north of Cathedral Grove, became BC's first provincial park in 1911. The carved Roosevelt elk on its entrance sign (above, left) hides the enormous resource sellout of wildlife habitat during the Park's century old history. Ruth Masters protested on the highway to defend Cathedral Grove in 2001 (above). She climbed the Comox Glacier in Strathcona Park in 1938 and for six decades has been a witness to the industrial plundering of the unique biodiversity of the 524,000 acre high altitude Park.

Roosevelt elk in Cathedral Grove, 2005.

Photo: Richard Boyce |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

"Ecosystems of MacMillan Park."

Government of British Columbia

Cathedral Canyon

Island Timberlands (aka Brookfield – Weyerhaeuser – MacMillan Bloedel) owns almost 260,000 hectares on Vancouver Island of "mature standing" trees that it boasts "are the best in the world." These added up to the biggest holding in BC and the second most valuable in Canada. Yet the company was caught in 2006 sneaking rare big trees by helicopter logging from Cathedral Canyon. After visiting the Canyon in 2006 (right), Port Alberni MLA Scott Fraser remarked that it "forms a natural biosphere link to Mount Arrowsmith and Cathedral Grove" and he warned that the public interests were no longer protected as a result of devious deals being made with the logging corporations. |

|

Cathedral Grove has been the object of many BC Ministry of Forests research projects such as "Ecosystems of Macmillan Park" (left) by A. E. Inselberg, et. al. The 1982 project was intended to maintain and "enhance the park's recreational integrity" as a remnant of old growth Douglas fir forest that was widespread prior to industrial logging. MacMillan Bloedel contributed to the study and not surprisingly advised silvicultural practices to manage the 90 hectare park even though such scientific forestry practices had virtually wiped out the ecosystem represented by the park.

Cathedral Canyon, 2006.

Photo: Scott Tanner |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

While the logging corporations engage in elaborate schemes to continue their unethical annihilation of the last ancient forest remnants on Vancouver Island, community members are searching for imaginative ways to try and protect what little is left by the forest destroyers, to ensure the longtime health of their watersheds. Friends of Cathedral Grove (FROG) member Phil Carson (right) reported in 2006: "We have already done a good deal of work on the concept of a National Park that would encompass the Beaufort Range up to Stathcona Park and protect the connecting corridor between the North and South Island. It is the Biosphere to Biosphere concept connecting Mt Arrowsmith to Clayoquot Sound." Drafted a decade ago with the Western Canada Wilderness Committee, the 200 page proposal "Linking Two Biospheres" was broadly supported by the local communities and is currently being revitalized. |

|

FROG member Phil Carson, 2006.

Photo: Karen Wonders |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

E&N Railroad Trestle built in 1911, Cameron Lake.

Cathedral Grove, Vancouver Island, British Columbia

In 1998 the Public Access Resolution Committee petitioned to obtain "Block 1380," to turn Mount Arrowsmith into a wilderness park. The BC Park Legacy Project of 1998 established recommendations for the management and protection of BC Parks, in large part to preserve the wilderness values that are the nature inheritance of future generations (right). The report was never implemented. Another citizen generated initiatve is the Arrowsmith Parks and Land Use Council, formed in 2009 with the goal of ending logging in the Cathedral Grove ecosystem. |

|

Another proposal is the creation of a "I-Treasure" communication hub in collaboration with the Mount Arrowsmith and Clayoquot Sound Biosphere communities as well as with First Nations. Cathedral Grove has huge potential as a site for nature tourism and for educating people about ancient forests and their destruction by industrial logging. One remarkable relic of the lumbering era on the West Coast is the Cameron Lake Trestle, built in 1911 of old growth cedar (left), today surrounded by second growth forests.

Boy fishing at Cameron Lake, 2008.

Photo: Guy Monty |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Totem pole and BC Legislature, 2006.

Photo: Karen Wonders

Cathedral Grove contains fine examples of indigenous heritage trees such as ancient red cedars (right) and culturally modified trees. Instead of honouring this big tree nature legacy which links the Mount Arrowsmith and Clayoquot Sound Biospheres and supporting local communities and ecotourism, the BC government caters to the logging industry and transnational corporations that are destroying the last ancient forests. |

|

BC's capital city, Victoria, is situated on the

southern tip of Vancouver Island, only a few hours drive from

Cathedral Grove. Up to a million tourists visit the world famous

big trees each year, many on their way to the spectacular wild

nature of Clayoquot Sound. On the grounds of the Legislative

Buildings In Victoria stands a magnificent totem pole, called

the "Knowledge

Totem" (left).

It was carved by Cicero August and his sons Darrell and Doug

August of the Cowichan Tribes and raised in 1990. This totem

pole and many others testify to the size of the

monumental cedars that are an icon of BC. Yet they also stand

as a reminder of the sad truth that the big cedars are being

annilhilated by the logging industry.

Ancient cedar tree, Cathedral Grove.

Vancouver Island, British Columbia |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Coastal Douglas Fir Forest. Pathway through Cathedral Grove, an endangered ancient ecosystem.

MacMillan Provincial Park, Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

©

Credits & Contact |

|

| |

|

|

|

|